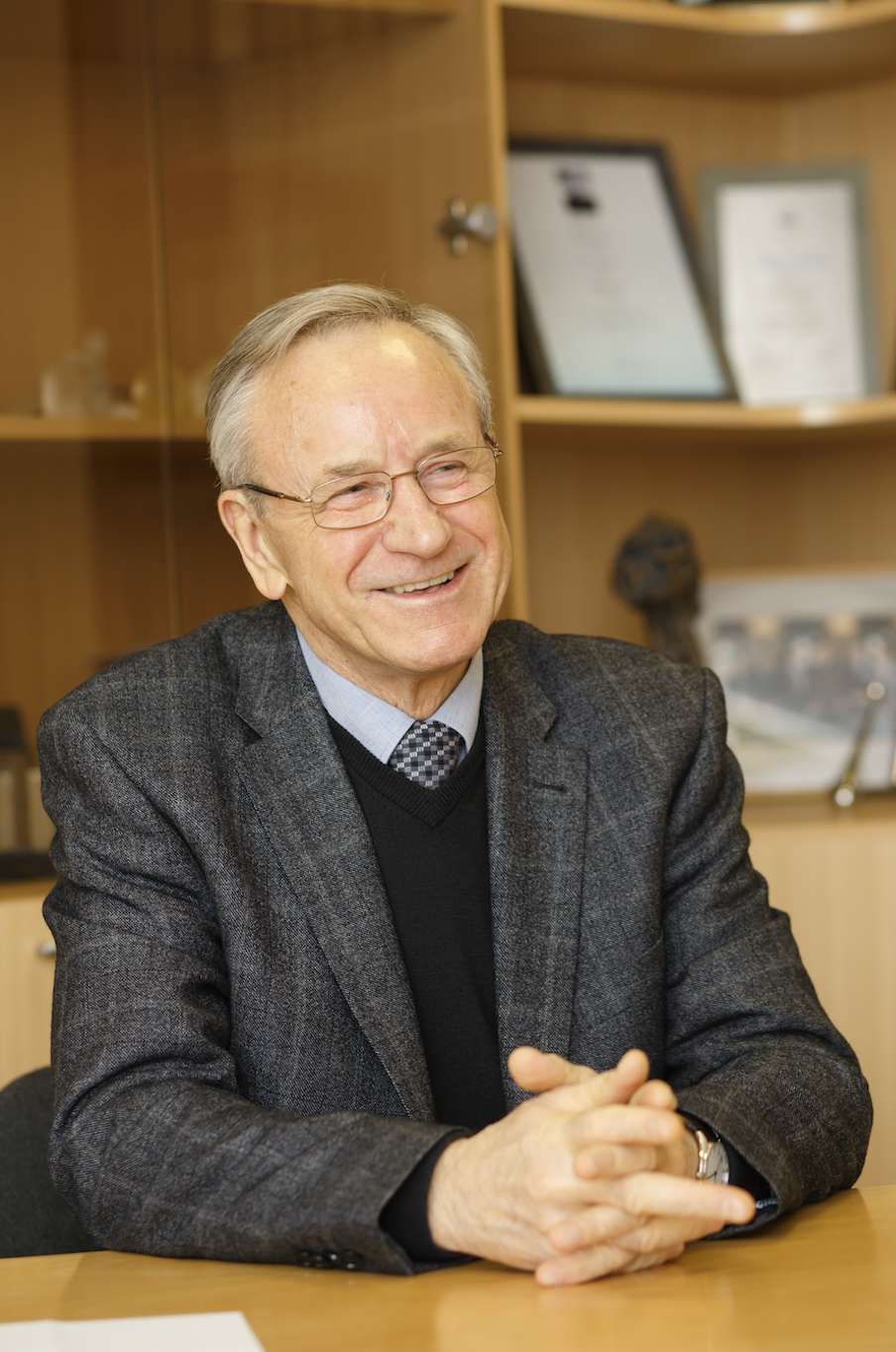

President of the Lithuanian Laser Association, widely regarded as the father of Lithuanian laser science

Lasers, Light and Vision: The Importance of Fostering High-Tech Innovation

“Curiosity, inquisitiveness, and a desire to explain various active phenomena encourage innovation,” says Algis Petras Piskarskas, President of the Lithuanian Laser Association, widely regarded as the father of Lithuanian laser science. He believes the country needs to avoid being distracted by other endeavors and instead focus its attention on creating advanced technology – technology that is making a name for Lithuania abroad.

Having completed his studies at Vilnius University and Lomonosov Moscow State University, Piskarskas returned to Lithuania, where he became a star who outshone physicists from Russia and the United States in the field of laser research.

What influenced your decision to go into laser research?

It’s impossible to reduce your motivations in life to just one factor because, of course, there are many. The field of optical studies drew my attention while I was studying at Vilnius University, particularly when the director of the math and physics department, Povilas Brazdžiūnas, conducted lectures on optics. He was an unusually passionate and charismatic individual, one who made a big impression on all of his students. Many fell in love with the subjects he taught, and I found myself among them.

At that time, my colleagues and I were building radio transmitters, and I even had my own radio station. On the air, I had the opportunity to interact with people from all around the globe, and it was then that I learned that light is an electromagnetic wave, an intrinsic aspect of my hobby.

Driven by great curiosity and Povilas Brazdžiūnas’ lectures, I began to seriously consider a future in optics.

We were competing with colleagues not only from Russia, but also from the United States. They were also creating lasers, but we were able to create better ones. Today, one in ten lasers used for research comes from Lithuania.

Algis Piskarskas

You later studied at Lomonosov Moscow State University?

That’s right. In my second year, the opportunity arose to continue my studies at Moscow State University. In the days of Soviet Union, certain academic spots were allocated to republic universities; a few students would be selected to study in Moscow. At the time, Lomonosov was considered one of the best research centers in the Soviet Union, and so, with the help of Povilas Brazdžiūnas, I departed for Moscow.

By mere coincidence, the laboratory to which I was assigned was conducting laser research, and – maybe because they were impressed with the radio apparatus I had built – they decided to give me a chance. This provided a unique opportunity to get in on the ground floor of a brand new scientific field. I began working there, and soon the job became the driving force behind my life.

While studying, did you ever think that one day you would be the founding father of laser research in Lithuania?

Oh, I really never had any such ambitions. While studying at the university, I maintained close ties with Lithuania, especially with Prof. Brazdžiūnas, but I had other aspirations. My intent upon returning was just to share what I had learned and take advantage of the international contacts I had made, but one thing led to another, and this laid the foundations for laser research in Lithuania. It was the only thing I knew how to do.

The beginning of this research, was it difficult? What were your biggest challenges?

It wasn’t easy. We had plenty of ambition, but equipment, financing and a location still needed to be found. Luckily, Prof. Brazdžiūnas was a great help, and the rector of Vilnius University in those days, Jonas Kubilius, was a strong believer in promoting new fields of research. He understood their significance for Lithuania.

Everyone knew if we wanted to be taken seriously in the Soviet Union, we would need to create something uniquely ours, and it was starting to happen. Hydroelectric and nuclear power plants were built, and laser research began to develop.

Through some old connections at Moscow State University, we succeeded in getting funding, but when we opened our first laboratory and started producing good results, that same university began to view us with suspicion. The displeasure only deepened when Lithuanian articles began to appear in international publications without the co-authorship of Moscow State University scientists. It was a competition.

You need to understand that it wasn’t a simple matter to get academic articles published. You first needed to get permission from the censors, so we hatched a plan. The instructions we received stated we weren’t allowed to publish any articles mentioning lasers of over one kilowatt, so instead, we would write that it was a 1000 watt laser. The censors wouldn’t always catch on, and the article would get the green light.

It was the same for our colleagues in other fields. For example, certain doctors wanted to perform the first heart transplant, but Moscow forbade it, for how could Lithuanians be the first ones to carry out a heart transplant?! And so it was forbidden.

We were competing with colleagues not only from Russia, but also from the United States. They were also creating lasers, but we were able to create better ones. Today, one in ten lasers used for research comes from Lithuania.

Forward – the most important thing is to not get complacent with our achievements.

Algis Piskarskas

From your experience, what does it take to create something new?

Aside from curiosity and inquisitiveness, you need a sort of sports-like enthusiasm. Researchers have a desire to be first, to do better, and to announce results sooner than their colleagues. In research, recognition is demonstrated through citations, announcements, and invitations to academic conferences. The motivation is both sporting and patriotic, in that if we’re working at Vilnius University, then we need to be recognized as Vilnius University, as Lithuanian scientists.

You also need to be faster than everyone else. If you’re late to publish, then you won’t be cited, and citations are incredibly hard to come by in the international scene since they bring not only honors and recognition, but also financing. If you’re late releasing a new product, you can go bankrupt.

When Lithuania regained its independence and opened up to the world, new streams of revenue and financing became available to us. The colleagues who were evaluating our projects’ funding requests already knew us from articles and academic conferences, so it was easier to get this support. This is how the development of internationally funded projects began in Lithuania.

Your achievements have inspired others. What inspires you?

This is a difficult question because, of course, everyone has certain motivations. For people like me, there is an overwhelming desire to create something new, to share my vision.

In science, what drives you is the desire to explain how certain phenomena really work. Later, the realization that you can expand on your findings through the development of new technologies continues to push you forward, and thus, innovations are born.

In the beginning, I studied certain phenomena that occur in clear crystals when they’re exposed to a laser beam. As it happens, when certain crystals are exposed to a particular color of laser beam, the color changes, and instead of one color, the whole spectrum of color can appear – the whole palate. In the beginning, these were only theoretical projects.

But this idea interested me to no end, and at Moscow State University, we succeeded in showing that this wasn’t just a theory – this phenomenon works in practice as well. When I returned to Lithuania, this research became my motivation.

What is the secret behind the Lithuanian laser industry?

Even though we were competing against America and Russia, we succeeded in creating a better product, which was the first seed from which the industry sprouted. The earliest industrial products to find a place in the market were based on that first model, and today the Lithuanian laser industry makes a range of products: one out of every ten lasers used in science is made in Lithuania.

We now have twenty-four laser industry companies, the most profitable of them being Light Conversion and Eksma. This segment’s success comes from the close relationship we have with scientists, industrialists, and professors within academic circles, especially those who are training specialists. The laser industry now employs close to 600 people, and most of them are our graduates. The high-tech laser industry segment draws many scientists, and one in ten is a PhD. You won’t find this in any other industry.

Who has taken the most interest in this market?

In 1993–1994, a third of our exports to Japan consisted of lasers. The Japanese showed interest in us because labor in Lithuania was quite cheap then. Today, 50% of our laser exports go to the European Union, and in total, exports make up about 95% of production.

In fact, foreign companies needing certain lasers, such as the Faros laser, have to wait over a year because the Lithuanian industry cannot manufacture them quickly enough to meet demand. This laser is particularly popular in Asian markets like China and South Korea because it can be used to cut elements necessary for computers. These lasers are very promising for the manufacturing of electronic accessories such as mobile phones and so on.

In science, what drives you is the desire to explain how certain phenomena really work.

Algis Piskarskas

At present, there is pressure not only due to the volume of orders, but also due to offers to invest in Lithuania and increase production volume. Whether this is in the country’s best interest is unclear; nobody knows if this interest masks an intent to take over our high-tech industry because of all the know-how and talent we have here. Such offers are on the rise, but for the moment we’re viewing them with caution.

We created our laser industry independently when we were part of the USSR. Later, we fought to be recognized as an independent nation. Maybe this is a hallmark of the Lithuanian character: either to be sovereign – or to fight for sovereignty.

Will you miss being involved in scientific activities?

I didn’t really leave. Instead, I was given a great gift by Vilnius University: the title of Professor Emeritus. We also continue to work informally on a few ideas I have from earlier projects.

Having dedicated my whole life to science, sitting at home with a novel doesn’t do anything for me. My entire life has been driven by that internal fire: the love for lasers. I have given so much of my time to them that it’s impossible for me to just stop. Perhaps I’ll return to lecturing.

What thoughts cross your mind when you look at your younger colleagues?

I’m jealous. I think if I had as much energy as them, I could do so much. But time continues to march forward. You can’t turn it back.

I’m very happy the younger generations are studying physics with such enthusiasm, and at least the emigration of physicists is small, because industry leaders are hiring them to work here. The future is in their hands.

So where should Lithuania go from here?

Forward – the most important thing is to not get complacent with our achievements.

According to Nobel laureate Abdus Salam, the greatest mistake is when developed countries push high-tech development aside in favor of traditional technology. It’s important to avoid jumping from one priority to another.

In Lithuania, we will continue surpassing our achievements, recognized both at home and abroad, and will reach even greater heights.