Dr. Norbertas Černiauskas

Lecturer at the University of Vilnius’ history department

Photo credit: Romualdas Požerskis

Wild Nation-Building

The political independence Lithuania declared in 1918 took a long time to solidify – not just behind the diplomatic scenes but in fighting that took two long years (1919-1920). Later, challenges of great urgency would await Lithuania. Having existed for over a century in the backwaters of the Russian Empire and only gaining liberation from a feudal economy and mental serfdom in the mid-19th century, the young nation had a lot of expedient work ahead of it. It was no accident that its people set about working, thinking and learning at a rapid pace – it was said at the time that the nation-building generation would have to overcome an entire century of economic, social and cultural backwardness.

The 7th Lithuanian Agricultural Fair in Kaunas

Photo credit: Janina Tallat-Kelpšienė, LCVA A028-P016

In truth, between the First and Second World Wars, Lithuania, in trying to catch up with the rest of Europe and make up for lost time, undertook enormous reforms. By 1922, agrarian reform was in the works covering the country’s entire territory and its hundred-thousand-strong population. On the back of this reform, Lithuanian farms began to lay their foundations, and seedlings of individuality, creativity and entrepreneurship began to take root in society. In 1928, with the consistent implementation of reform that made primary education compulsory for all, tens of thousands of children began to attend school, learn about the world and love their country.

Without the possibility of keeping the historical capital of Vilnius, Lithuania created a new one – Kaunas, replete with modernist architecture and a Western spirit. Many other tasks were also completed: a tricolour flag was designed, a university that would shape the intellectual face of the country was founded, and Lithuania for the first time in its history became a maritime nation – a recovered coastline allowed the port of Klaipėda to thrive as a citadel of trade. Let’s also not forget that the stable currency was created, a network of modern schools and dairy farms was established and the first Universal Encyclopaedia was published. By 1937, Lithuanian readers could choose from as many as 17 national daily newspapers.

Most importantly, the modern Lithuanian state built from 1918 to 1940 was based on principles of equality, freedom and welfare for all citizens, which meant that for the first time all who chose to live in Lithuania became builders of the nation state.

Norbertas Černiauskas

The mixed-structure two-seat monoplane with a strut-braced wing ran on a low-powered air-conditioned 5-cylinder radial engine and was used for training pilots. Its maiden flight took place on 10 November 1927. After undergoing repairs, ANBO II was handed over to the Aero Club of Lithuania. It was used by the club and by the Lithuanian army until 1934. Only one prototype was ever made. Engineer: Antanas Gustaitis.

Antanas Wants to Fly

Having found its feet and stood up alongside its fellow European nations, the Lithuanian state undertook countless projects so it could demonstrate to itself and to others its uniqueness, its modern achievements and its economic potential. In the long run, the nation came to realise that for all of its traditions and customs, magnificent tales about a historical Lithuanian state that stretched from sea to sea 500 years ago, and a longing for the lost city of Vilnius, other nations had similar stories to tell, and besides, these historical episodes didn’t seem much like the exceptional ambitions of a state in a modernising world.

The country’s aviators took it upon themselves to write the first Lithuanian success story, inspiring a society of pragmatic farmers to believe in the meaningfulness of heroic deeds. In 1933, the Lithuanian pilots Steponas Darius and Stasys Girėnas successfully flew over the Atlantic Ocean only to tragically die in Germany. Another phenomenon – ANBO (Antanas Nori Būti Ore, Eng.: Antanas Wants to Fly) – was not just a modern aircraft for the Lithuanian air force built by General Antanas Gustaitis but a manifestation of the Lithuanian dream – the desire to be one step ahead and prove the creative potential of a small, young nation. By the late 1930s, ANBOs made up more than half of the air force’s fleet.

In 1937, with no athletic achievements or traditions to its name, Lithuania once again surprised Europe by winning the European Basketball Championship with an improvised national team of local residents and US émigrés. In 1938, the Lithuanian women’s team stepped onto the podium as vice champions of the Old World. Overcome with euphoria and in record time, the country built the Kaunas sports arena, the most advanced of its kind in Europe, and in the subsequent 1939 championships hosted by Lithuania the national team beat the other European teams for the second time in a row. Incredibly successful as a public relations project that united Lithuanians around the globe, these events gave rise to Lithuania’s unique basketball traditions, which thrive to this day.

The Green Team of the Sierakauskas District in the Vytis military region was established in August of 1951 (32 fighters were enlisted). The team operated in Pandėlis District, Biržai District, parts of Vabalninkai District (formerly the districts of Kupreliškis, Nemunėlis Radviliškis, Parovėja and, in part, Papilis District) and on Latvian territory.

LYA K-30. 1. 714. Photos 367-7.

Decade of Hideouts

In the mid-20th century, a sprawling network of hundreds of hideouts, bunkers and other unusual infrastructure projects worked its way across Lithuania. These were not built with the intention of preparing for a mass evacuation or a natural disaster – the lives, fates and memories of thousands of people would depend on the inventiveness and sturdiness of these structures.

The nazi and soviet regimes of 1939-1953 and the crimes they perpetrated – the Holocaust, various massacres, imprisonment in concentration camps, deportations, forced mobilisation and collectivisation – led to the loss of millions of Lithuanian lives. For over a decade in this atmosphere of universal distrust, the desire to survive, resist, refuse to come to terms with the regime and preserve human dignity often intertwined with the temptation to collaborate, conform and betray. For many long decades to come, traces of this collective trauma would keep coming to the surface.

From 1941 to 1944, the first hideouts (malinas*) were built en masse by Lithuanian Jews who had managed to escape ghettos set up by the nazis and their henchmen. One alternative for refuge, survival and even resistance was the underground cities that began to develop beneath the ghettos of Vilnius, Kaunas and Šiauliai. Here, families found refuge, dissidents held meetings and communities hid objects of cultural value and weapons. To this day, the ghetto hideouts serve as a reminder of the tragedy of the Holocaust and the people’s attempts to survive as well as preserve accounts of the terror they suffered for future generations.

Malina originates from ‘melina’, the Ivrit word for hideout or ‘meluna’, the Yiddish word for cave.

Later, this network of bunkers spread across the country’s forests and countryside. During a partisan war with the USSR (1944-1953), Lithuania’s freedom fighters set up hundreds of hideouts, bunkers and semi-open camps. At different times of year, these hideouts in forests, wells, houses and farm buildings could house up to several thousand men and women. Even though from an engineering perspective the hideouts and bunkers were rather complex, life inside them was hard, and if the enemy surrounded them the chances of getting out were slim. Despite this, the bunkers were alive with more than just day-to-day action – they saw the underground press in action and critical political documents signed by the leadership of the resistance movement.

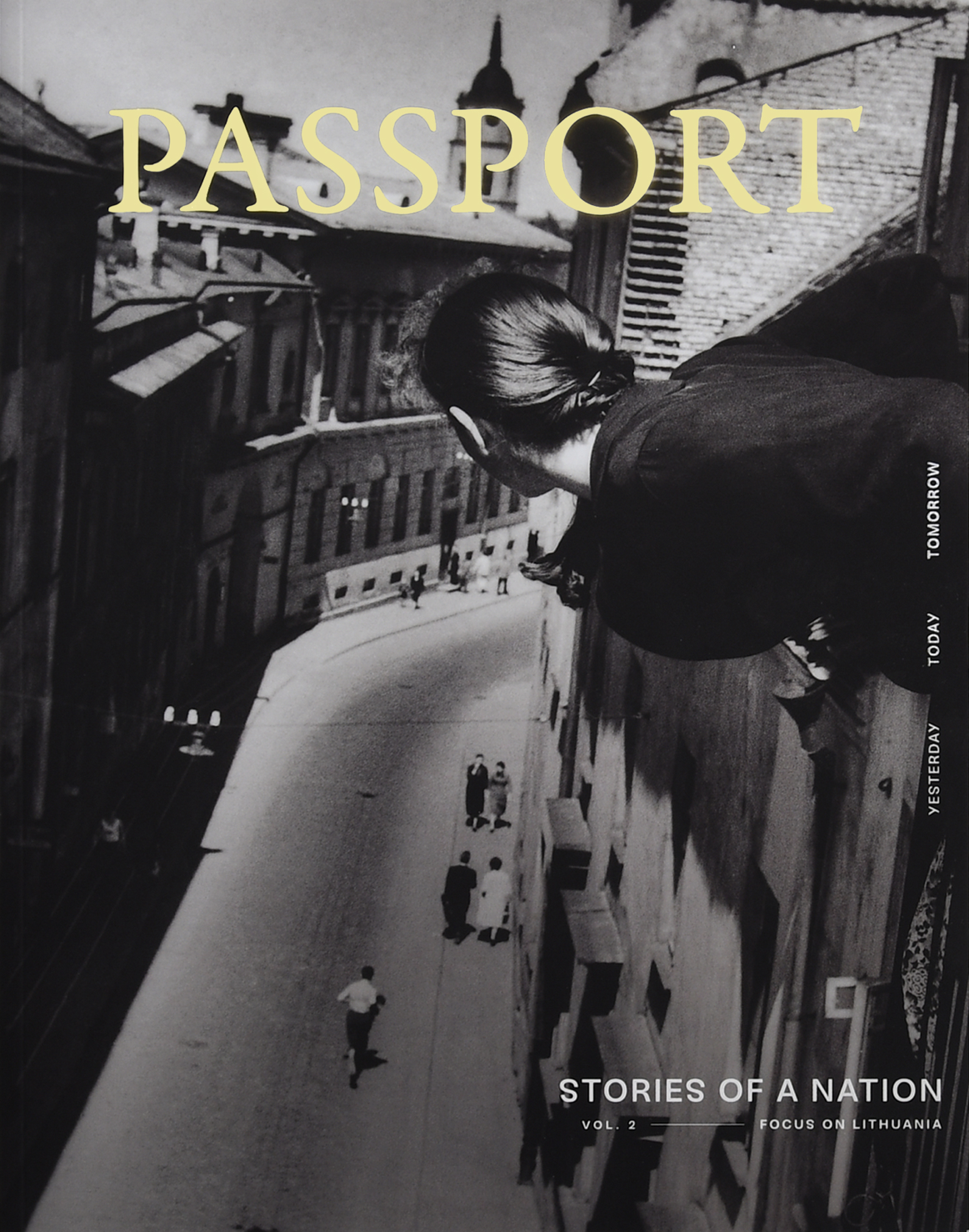

Photo credit: Romualdas Rakauskas

Breadless

The renowned twentieth century Lithuanian poet Marcelijus Martinaitis used a single word to describe life in soviet Lithuania in the 1950s – breadless. This was a life of half-starvation that meant only the most critical human needs could be met.

There was frequently a shortage of food, clothing and household goods, not to speak of immaterial human needs.

Norbertas Černiauskas

The situation cannot be explained through the political terms of the soviet occupation and annexation alone. Of course, sovietisation meant a change in the political order (Lithuania was annexed by the USSR), but it also meant drastic changes in the daily social and economic life of the people. Soviet reforms touched the majority of the people and were implemented through the collectivisation of the farmland. The confiscation of personal property, the erosion of traditional rural communities, the restriction of independent initiative and the establishment of the kolkhoz (collectives) as well as standardised kolkhoz communities on an ideological as opposed to economic basis disrupted the lives of a large part of the population. In other words, the farms that were established from 1920 to 1940 by the settlers and farmers of independent Lithuania, helping the national economy produce substantial quantities, were systematically destroyed with a view to throwing into disarray the well-developed sector of Lithuanian agriculture – a prime target for the communist regime.

From 1950 to 1960, the greater part of the rural populace could no longer remember the taste of meat and bread. Urban grocery stores no longer had anything to sell and the 3,000 daily calories per capita boasted of in independent Lithuania were a distant dream. When they could no longer support themselves, larger families fled to the cities in the hope of finding work in the industrial and construction sectors. Lithuania had once been renowned for its agricultural output, yet the economic policies of the USSR, even after Stalin’s repressions came to an end, led to one of the most difficult decades in Lithuanian history. The transition from war and repression to universal poverty, the further spread of soviet ideology, an increasingly conformist society and attitudes of indifference gradually gave birth to a new species of citizen – homo sovieticus.

Photo credit: Romualdas Požerskis

Progress, Industrialisation and the Space Race… Blat, Deficit and the Nomenklatura

The 1960s marked a culmination of communist progress that swept across the empire and its population. The utopian ambitions of the soviet leaders and the Space Race went hand in hand with large-scale communist construction projects. In Lithuania this meant rapid industrialisation. Identical high-rise apartment blocks shot up across the country, urban infrastructure projects were launched and grand industrial development and electrification programmes were implemented. Children dreamed of becoming astronauts and tasting chewing gum for the first time, adults imagined the completion of the five-year plan and getting a communal apartment, and the political elite fantasized about overtaking the capitalist world and securing an allowance for a new car.

Most of the daily decisions made by the local regime were made not in consideration of the public’s expectations but with the aim of cosying up to Moscow and negotiating personal gain. When speaking of soviet progress it should be noted that throughout the entire soviet space the general principles of modernisation also had a strong ideological component. Urbanisation was implemented according to the maxim ‘faster, cheaper, more’, while any potential individuality was repressed. For example, flats were designed with as little personal space as possible, with pass-through rooms and very small kitchens.

Despite the drastic changes in the urban and agricultural landscape, contradictions in the official and actual lives of ordinary soviet citizens began to become apparent. While declaring its triumphs in space and its unrelenting progress, the union suffered from bribery and a deficit of food and household goods, and the looting of state assets was becoming a widespread practice – an alternate reality was taking shape, one in which the quality of life was determined by personal connections and blat. The communist party nomenklatura and its immediate environment took great advantage of various privileges, from specialised grocery stores reserved just for them to special-access hunting grounds. In the 1960s, the ruling class of the LSSR could boast of the fact that the majority of the population lived in the cities and had electricity, gas and running water in their homes. However, the saying ‘think one thing, do something else and tell everyone that you did yet another thing’ became an integral part of soviet life.

Blat is a favour-based form of corruption, where personal connections are used to make illicit deals for the procurement of desired positions, services or deficit products.

Nomenklatura describes a group of privileged individuals who held influential administrative positions in the Soviet apparatus.

Left to right: Vincentas Vėlavičius (1914-1997), Alfonsas Svarinskas (1925-2014), Sigitas Tamkevičius (b. 1934), Juozas Zdebskis (1929-1986), Jonas Kauneckas (b. 1938). The TTGKK was founded on 13 November 1978 and operated in the open, its purpose to call public attention to the discrimination against Catholics. When Svarinskas and Tamkevičius were arrested in 1983 and ‘preventive’ measures were taken against the remaining members, the committee’s operations moved underground. Zdebskis was killed in a car crash in mysterious circumstances.

LYA K-1. 58. 47753/3. 336-1. Photo 9.

Mission Impossible: the Undisrupted Anti-Soviet Chronicle

For Lithuania, 1972 was marked by Romas Kalanta’s self-immolation, the waves of anti-soviet stirrings among the young people of Kaunas this gave rise to, and the first publication of the underground Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania (Lietuvos katalikų bažnyčios kronika or LKBK). The chronicle was printed under incredibly difficult conditions all the way up until the eve of independence in 1989, making 17 years of uninterrupted publication under the oppression of the evil empire seem like a miracle to this day.

Even the all-powerful KGB failed to track down its editors, publishers and distributors.

Norbertas Černiauskas

A broad network of agents and informers, constant searches of suspects’ homes, arrests and violence perpetrated against individuals assumed to be connected with the chronicle did not prevent its publication and distribution.

Even when Sigitas Tamkevičius, priest and principal editor, was shipped off to work in a labour camp in 1983, the mechanism did not fall apart and the process continued, with another priest, Jonas Boruta, taking over his duties as editor. The publishers of the chronicle also achieved what then seemed like an impossible mission – with the help of Russian dissidents, they broke through the Iron Curtain and distributed the publication internationally.

What does the 81st edition write about? The chronicle recorded and publicised the facts about the discrimination and persecution of the church and its believers in Lithuania, and wrote about violations of human rights and the arbitrary self-will of the regime and its crimes. The publication of the LKBK was one of the few things that stood out as a bold alternative to the conformity-enforcing and complicity-inducing brainwashing undertaken by the totalitarian regime. If alongside the phenomenon of the chronicle we count the politically active Lithuanian émigrés, the group of anti-soviet non-violent dissidents led by Antanas Terleckas, manifestations of dissent in the 1970s and the idealists and realists who began to take a stand in soviet society and who maintained an internal human decency and loyalty to the vision of Lithuanian sovereignty, we will have a general notion of this alternative space, in which the idea of freedom and independence had a chance of survival.

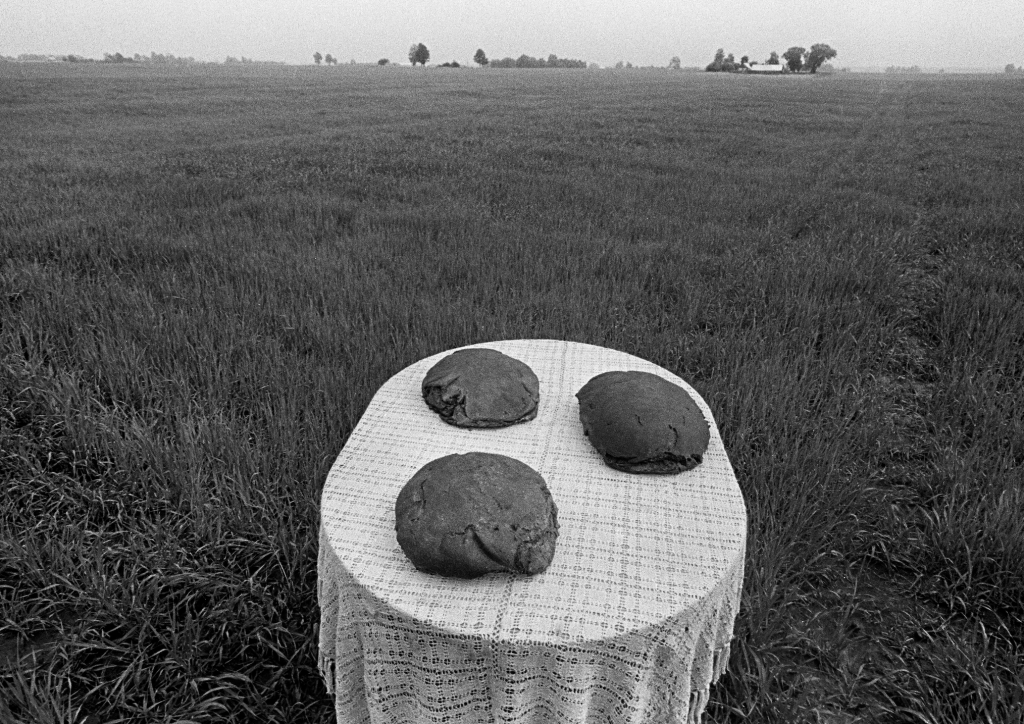

The first unsanctioned event of its kind in soviet Lithuania and the first public anti-soviet demonstration since the events of 1972 in Kaunas.

Photo credit: Martynas Ambrazas

Afghanistan, Chernobyl and the Breakthrough by the Mickevičius Statue

At first glance, 1980 looked to be an optimistic time. The Moscow Olympics failed to stir the USSR from its stagnation and the military intervention in Afghanistan initiated in 1979 sank the soviet realm into an ever-deepening financial and moral quagmire. For almost 5,000 Lithuanians who served on this mission, much as for all the other conscripts in the army, the word Afghanistan meant the unknown, physical violence and a meaningless death. In general, compulsory enlistment in the army of the USSR was associated with the widespread phenomenon of dedovščina* and led to psychological trauma for several generations of young men.

*Hazing

In the 1980s, life in the USSR was also significantly coloured by another event – the 1986 atomic catastrophe of Chernobyl. This was the final nail in the coffin of the myth of Soviet technological progress, and attempts to keep knowledge of the event under wraps and the regime’s inability to effectively deal with the consequences revealed the colossal scale of the deceit and ineffectualness of the soviet system. Mikhail Gorbachev tried to reform a USSR plagued by radioactive clouds and stagnation, but despite further industrial development and cosmetic democratisation, the economy fell into a recession that could not be saved by Siberia’s vast natural resources and cheap labour force or the encouragement of competition in the socialist race.

Even though the situation in Lithuania in the 1980s no longer resembled what its citizens had to endure under Stalin, and many adjusted to the existing political system and simply lived their lives, the need for fundamental change was obvious.

But the silence of stagnation could only be pierced by the most courageous voices, those of the long-suffering dissidents.

Norbertas Černiauskas

On 23 August 1987, the underground Lithuanian Liberty League brought together a thousand-strong crowd next to the statue of the poet Adomas Mickevičius in Vilnius for the first unsanctioned public protest. After many decades of propaganda, the information blockade was broken. The participants openly discussed the illegal nature of the occupation of Lithuania and the many soviet crimes. From that day the political events unfolded and an unstoppable avalanche of change ultimately ended with the restoration of Lithuanian independence on 11 March 1990.

Restoration group of Ghor Province, Afghanistan

Photo credit: from the LRKAM archives

Euro-Atlantic Lithuania

If we were to name all of the terms that have a geographical as well as political meaning and have been at one stage or another used to define Lithuania’s borders – its size or condition – the Euro-Atlantic dimension would no doubt be the most robust of all.

From the formation of the Lithuanian state in the mid-13th century until the late 20th century, one of its main goals had always been to closely integrate with and become a part of Western (European) civilisation. It’s no coincidence that Lithuania’s most successful points of statehood throughout its 800-year history were related to successful projects of Europeanisation: the country’s Christianisation in 1387, the foundation of a university in Vilnius in 1579 and the introduction of a democratic constitution in 1922; while its lowest points coincided with shifts into the Eastern space and the occupations of 1795-1918 and 1940-1990 that came with them.

With this historical experience, the clear and purposeful orientation of the Lithuanian state towards Euro-Atlantic structures – the European Union and NATO – formed the basis of essential internal and foreign policy once independence was restored in 1990. The balancing of the political scales of this young democracy and the period of hardship that affected the entire post-soviet geopolitical space – the transition to a free market economy, the fall of commercial banks, the rise of organised crime, a feeble civil society, growing emigration – did not overwhelm Lithuania’s strategic, political and moral direction, and in 2004 Lithuania became a full-fledged member of the EU and NATO.

21st-century Lithuania is small in territory but its potential for action has never been greater. At the turn of the century it successfully integrated into the world’s most important structures, acquired the greatest guarantees of security (since 1253) and took on a significant role in the creation of a global defence system.

Today, the Lithuanian flag hangs at the headquarters of the United Nations, the European Union and NATO.

Norbertas Černiauskas