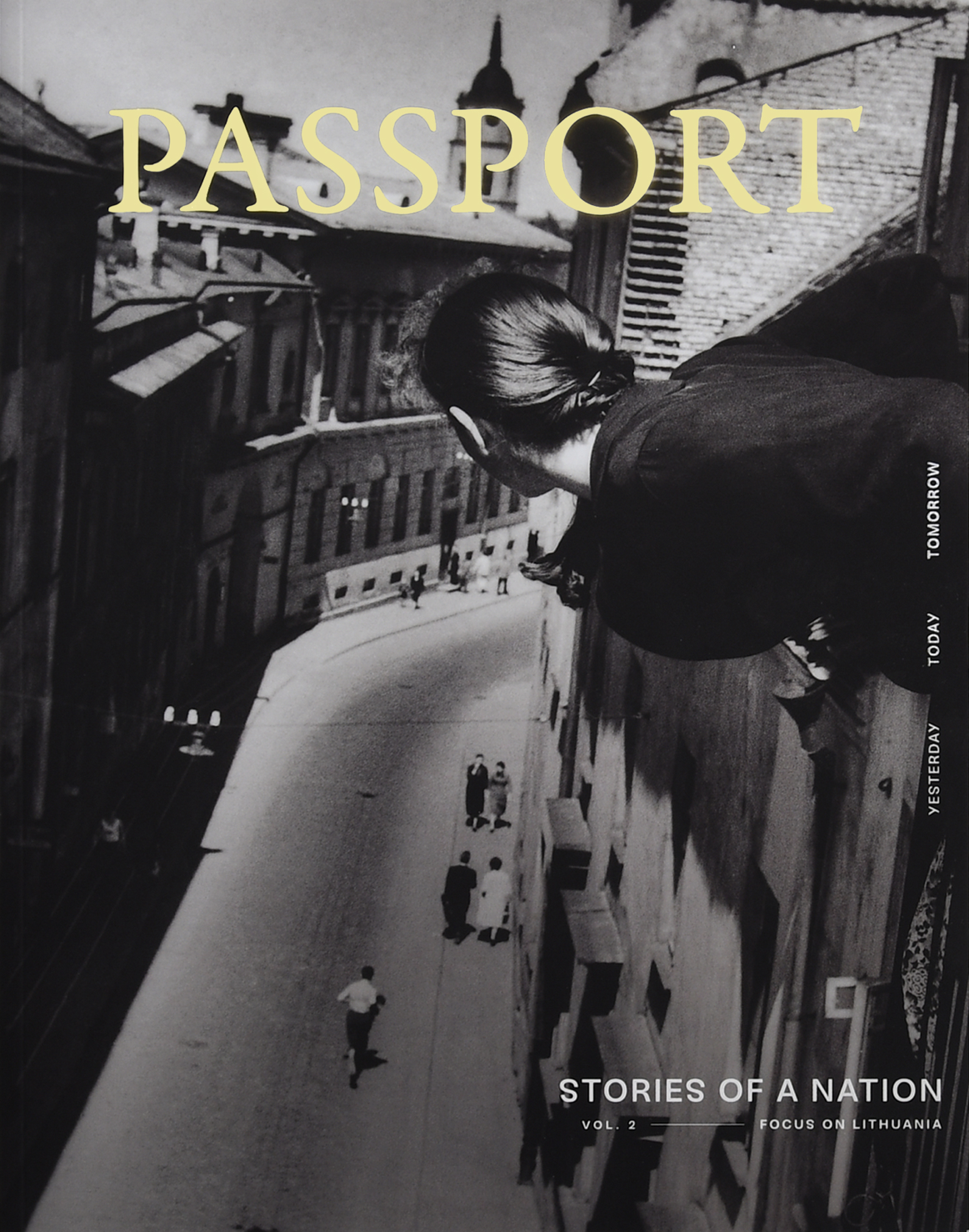

Cartoonist

Once I met the singer Harry Belafonte. He walked into my studio, gave me big bear hug and then said, “I was expecting a black man. God has a sense of humour,” recalls the South African Litvak Jonathan Shapiro, better known as Zapiro, the internationally recognized cartoonist and political commentator who opposed apartheid.

Jonathan Shapiro

THE COURAGEOUS ART OF ACTIVISM

You work as a cartoonist for more than 30 years. How did it all start?

I did some cartoons while I was studying architecture at the university. I did a cartoon of the lecturer and it was strongly satirical. I showed two sides of him and he didn’t like that. So that cartoon got a lot of attention, and the lecturer reacted to it publicly. But he did it in a way that made him look very stupid. And suddenly I said to myself, “Yes, I really can do this”. Later, at the beginning of 1994, I was phoned by the Mail and Guardian newspaper, which was an alternative newspaper that became very important. They called me and said, “Would you like to be our cartoonist?” That’s what I’d always wanted and I agreed. So from the beginning of the year in which Nelson Mandela became president, during the whole run-up to the presidency and the African National Congress taking over… That’s when I started.

What’s the connection between your cartoons and political activism?

I’ve been a cartoonist for a long time, but I really started out more as an activist than a cartoonist. There was military conscription going on in apartheid-driven South Africa and at the same time I decided to give up architecture, study graphics and become a full-time cartoonist. I didn’t want to join the army, so I had three weeks to decide – do I leave the country or do I go to jail? I thought, well, I’ll go to the damn army. I went, but I refused to carry a gun and that’s what turned me into an activist. The army officers really tried to antagonise me because I was refusing to carry it on political grounds. After six or seven weeks of persecutions I was given a fake rifle to carry – I sort of felt myself becoming a walking cartoon and it was part of my persona. But I was still in the army while I was doing a lot of stuff. There was the United Democratic Front, which I joined, and within a few weeks I was arrested. I started doing cartoons for anti-apartheid organisations that wanted to end military conscription. In fact, I designed the logo for one organisation, called the End Conscription campaign.

You personally knew people like Nelson Mandela, what does it mean to you?

This is a big standout and sort of recognition from my angels. I was jailed in the same prison as Nelson Mandela and other important political figures of the time. I’ve had incredible interactions with politicians and with society in general being hugely accepted as a commentator who’s doing my job. That is the most incredible thing.

Wasn’t it hard to stay sharp and critical having people like Nelson Mandela endorsing your work?

It’s hard to be critical when you’ve got somebody like that. I actually had to find a way to do cartoons that were not only supporting the ANC but also being constructively critical, because it was a very interesting period, from 1994 onwards. However, I had a wonderful relationship with some of the top people in the country and they accepted the criticism, especially Mandela himself. Once he phoned me to discuss a change at the newspaper where I was printing my cartoons, and before we ended the conversation I said to him that I was not only amazed that he called me but even more so because in the four years since I’d met him he had seen the cartoons getting more and more critical of the ANC and the government. Yet he replied, ‘But that is your job’.

What drives you most while working as a full-time cartoonist?

Moral outrage is what drives a cartoonist. As long as you are passionate about what’s going on around you, you are going to have attitudes. You wake up in the morning and see something that makes you go, “How the hell could that happen?” That’s a motivation for a cartoonist. And I never lost my sense of that.

What is your connection to Lithuania?

Well, both sides of my family have Lithuanian connections, my father enormously so as his family came from Lithuania to South Africa in 1906. His grandfather had already arrived in 1896, he’d been here for quite some time to get things set up, then the family came. They lived in a shtetl* called Plungė and I was there a few years ago for a British television series. There’s not much left of the look and feel of how it was, and where my grandfather’s house was there’s now an apartment block.

*A shtetl was a small town with a large Jewish population which existed in Central and Eastern Europe before the Holocaust.

How did it feel to go back to ‘the old country’?

When I went to Lithuania it was an unbelievable eye-opener. There’s a strange gap in my experience and I think it’s the same for some of the other people of my generation. My grandparents never really talked about Lithuania. They always wanted to make a new a life for themselves in South Africa and kind of forget what trouble it was – the pogroms, the economic hardship. I did feel an element, I don’t want to say anger because it’s too strong, but I resent a little bit the fact that I don’t know anything, that nobody really talked about it. I also wondered on my own, I still do.