Aušra Mikulskienė

Guide

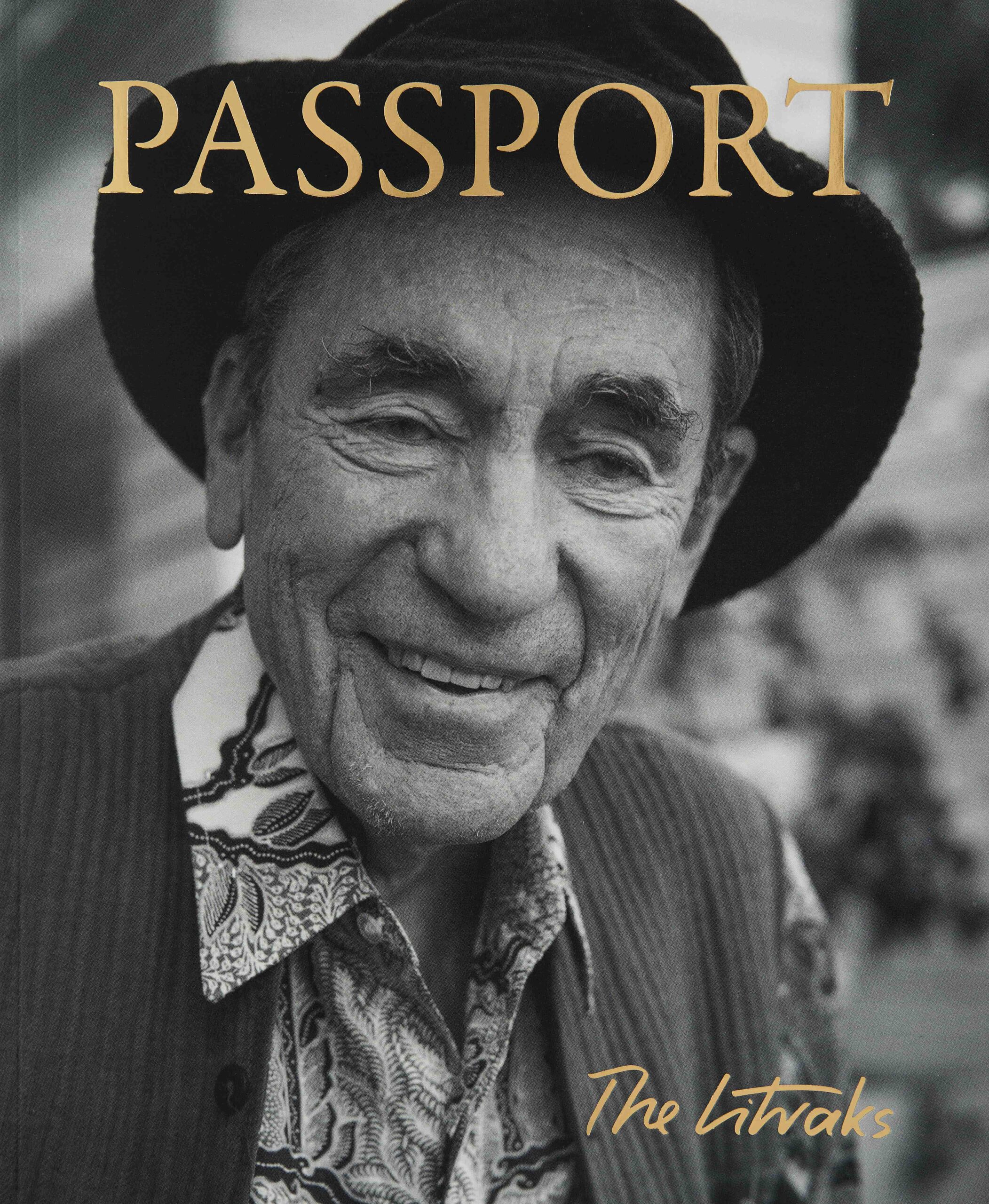

“You know more about my family than I do,” said my 70-year old fellow traveller with tears in his eyes as I turned onto the road for his grandparents’ birthplace of Rietavas which was on the way from Klaipėda to Vilnius.

Aušra Mikulskienė

At the time, I didn’t know the particulars of his family, but from that moment on, I began to take an interest in every single Jewish traveller as if they were a part of another family.

I am a tour guide who lives in Vilnius and I started taking an interest in Jewish heritage quite by chance. I would get inquiries from tourists to accompany them to Vabalninkas. They wrote Obolnik, so it took some time to for me to decipher which town that was. Then to Musninkai, to Kelmė. I’m not one of those guides who can take people where they’ve never been before and improvise on the spot, so I began to travel myself.

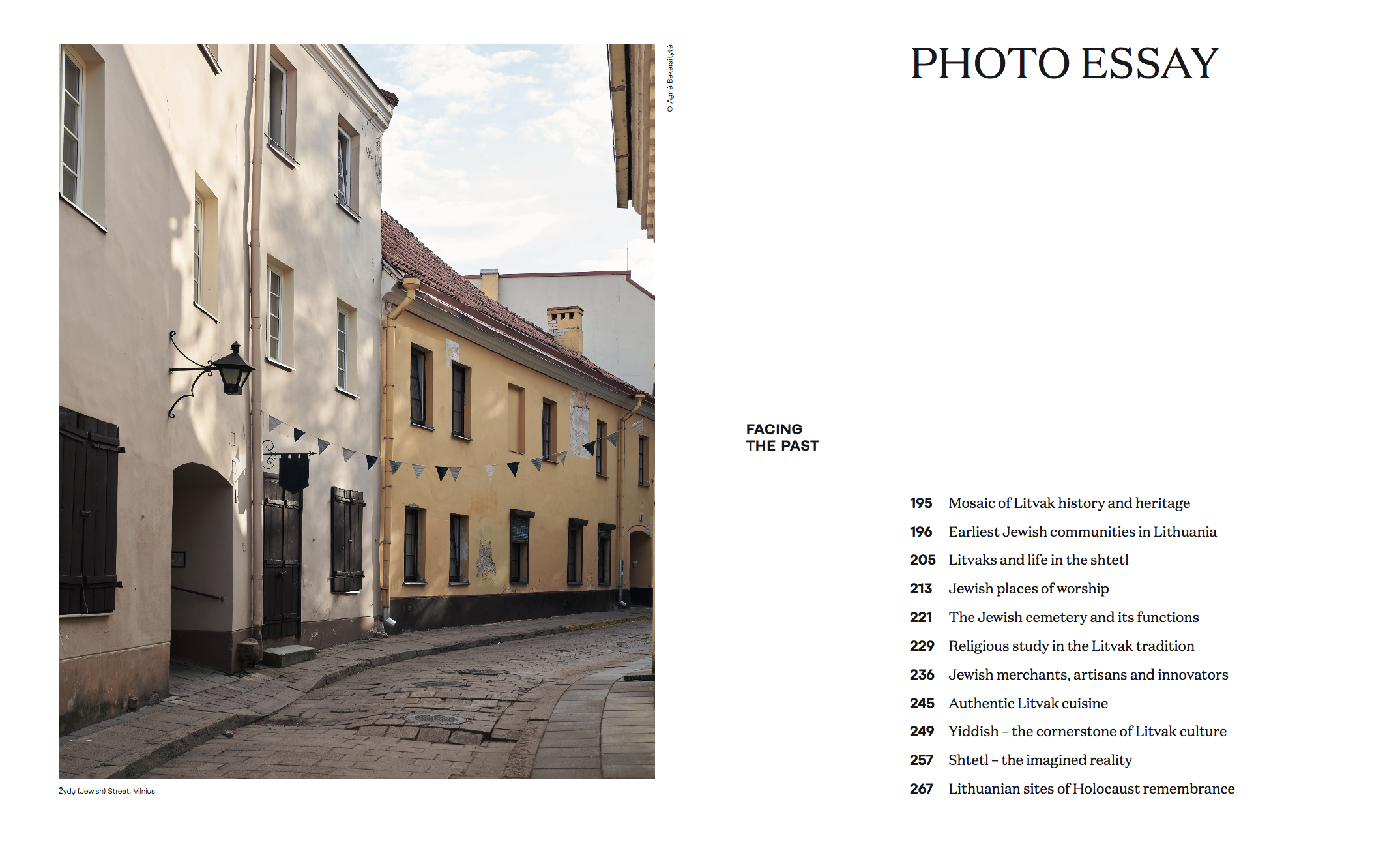

And so, over the course of four years, I visited hundreds of Lithuanian towns – former Litvak shtetls, virtually all of the over 100 synagogues that are known to have survived. I photographed old marketplaces and buildings that had been Jewish shops, schools and houses. I walked through cemeteries and combed the woods to find the small memorial plaques that mark the places where mass executions took place.

I am horribly sad about the latter and I don’t know how I can change anything. I’m not exaggerating, but in order to place a stone of remembrance near sites where victims of the Holocaust were buried, I had to wade through rivers, jump over mounds in swamps, plow through fields of grain, cross onto privately held land, climb over fallen trees, wander for hours along an inaccurately marked route. More than once I had to drag out an SUV that was stuck and then bandage up my injured legs. These trials cannot begin to compare to the suffering that was endured by those who were walking to their place of death, but the least that we can do to memorialize the 200,000 people who died is to ensure that those places be known, taken care of and easily accessible.

As sad as the history of the end of Lithuanian Jews is, there was certainly life up until the Holocaust. During my trips through former shtetls, I do my best to find and record memories of that life. I visit the sites of mass executions so that I can once again remember the stories of the innocent people who died and try to imagine how we would be living together with them today.

Love

I love all of those former shtetls. All of those beautiful synagogues of which only rubble remains and those that no one even remembers where the Jewish place of prayer was located. Those where heritage is encouraged and those that await its collapse. Those who build monuments, organize events, publish information and search for, research, create, decorate and those who have doubts about their Jewish history. Those where the grass in the cemeteries looks just like the lawn at the Presidential Palace and those for which you need to take along your own lawn mower. Those in which the path to the Holocaust memorial is laid out as smoothly as a carpet and those where you are more likely to break your neck than reach the place of mass executions. I am happy and proud of some of them, sad and ashamed for others, some I worry about, but I love them all.

Travel

“Take me with you on your trips,” a friend will say to me after reading another one of my descriptions on social media. “I saw that you were in Šeduva, why didn’t you stop in?” asks another after seeing a photo of me with an elderly woman from Šeduva who worked as a nanny for Jewish children and who learned to count in Yiddish from them. And I don’t have an answer. My trips are so spontaneous and so intense that including someone else to come along or to add a stop for a meeting would be very difficult. When I take it upon myself to find something, I’m afraid to tell anyone how long it all takes. I’ve started with a photo from 1935 which depicts a school that was a part of the Tarbut network. Another time, from a hand drawn plan drawn from memory. I’ve also determined the location of a former Jewish mill that was rebuilt into an apartment building and I found the house where the director of a Jewish Folk Bank branch lived until the war from a video of an interview that was shot during Soviet times. These are all parts of my journeys, my adventures, my experiences and I doubt that I will ever have a fellow traveller.

I rarely plan a trip the night before, but if that occurs, I leave enough time for early morning improvisations. I’ll get up at 6 AM and go wherever the weather reporter says that the sun is shining. Sometimes, when I’m already at the station, I choose whether to travel to Rokiškis or Lazdijai, Varėna or Radviliškis. When there’s an event planned at the far end of Lithuania, I take the most circuitous route to get there so that I can take at least a few pictures of shtetls that I have not yet visited. Sometimes I have a clear goal and itinerary but am waiting for the right time on any day except a Saturday. It would be disrespectful to be doing research on Jewish heritage on the Sabbath.

I like to travel by trains and buses, especially on longer trips or to bigger cities. My hands are free on a bus, I can read, take notes and plan my trip in detail. A golden rule for me is that the better I plan my trip, the less my feet suffer and I’m able to see more, so I prepare very carefully. I drive a car only when I’ve made up a very extensive itinerary for visiting smaller towns and I have to visit many locations in a short amount of time.

A small orange backpack for unexpected sleepovers is always on call in my closet: if needed, I can be ready in 15 minutes. The most important thing to remember is to take my chargers, laptop and some books. I’ve accumulated a very large library of books that contains practically everything that has been written about the Litvak shtetl communities both in Lithuanian and English.

A thermos of coffee and a box of snacks have become my steadfast companions and have saved me many times since it’s not always possible to find a place to eat and, very often, time starts running short as well. I really like to stay at local hotels. This allows me to not only get better acquainted with the town’s history, but to also experience the pleasure of changing out my home environment.

When I reach my destination, I always stop by the Tourism Information Center, the Regional History Museum and, if I need some additional information, I’ll go to the library. The libraries in towns have ethnography sections that usually have collections about their local Jewish community. Over these past few years of my research, I’ve acquired a pretty good data base of those who know about their Jews and those who don’t.

Jewish Heritage

Some skeptics may say that there are almost no Jews left in Lithuania and that there is practically no heritage. They’re probably right. Jews haven’t lived for a long time in houses that had their doors nailed shut, porches bricked in and roofs changed. The synagogues which during Soviet times were converted into grain warehouses, basketball courts or film theatres, are now full of pigeons flying about, birches growing out of cracks and you can count the stars at night while staring out through the holes in the roofs. There are only a few remaining headstones in cemeteries and those are covered in weeds that are waist high. Young people have parties with loud music and beer at cemeteries that are more isolated, not having any idea what had happened there and that their great-grandparents were the same age as they are now.

But for me, Jewish heritage is more than that. It’s the history of a person who lived here. That Joškė, who would treat the chidren of the peasants who stopped by his smithy with candy wrapped in rustling, prettily colored papers.

Aušra Mikulskienė

That Codikas, whom everyone called “the bagel man”, who would tie two extra mini bagels onto a string of five as a gift so that the buyer would come back. That Velvkė who waited impatiently for market day because then he wouldn’t have to go to school and instead could watch the farmers with their carts coming into the center of town from all directions. That little Leiba whose teacher had imbued in him a love of Israel from first grade so that he went on to study Hebrew and send all of the profits that he made from selling his handicrafts to the establishment of the state of Israel. That Sonya and her girlfriends, whom the neighbor boys would scare when they suddenly jumped out from underwater in the town’s pond. That Chaim Mordechai who left for overseas on a train from this very station to seek his fortune and never returned.

It is these stories that compel me to find this heritage that has been lost and to resurrect it from the past. The details of these stories round out the fragments of memories that my tourists have about their relatives and thereby complete them. They bring out their tears and force them to think about the fact that I do know more about their families than they do.

Locals

I’ll probably disappoint you, but I have almost no interaction with people on my trips. Why is that? Aren’t they more interesting than buildings, memorials or headstones? Perhaps, but then you become obliged to them. You have to find them, come to terms, talk about your research, make promises, listen and finally, you are obligated to believe them and see stories through their eyes. I don’t have that kind of time and don’t want to hear the memories of other people. People often make mistakes, repeat the opinions of others and remember only that which they want to remember. I need objective, historical facts and my own subjective emotions without the impressions of strangers.

No doubt, I do meet some local people. Some of them are very suspicious. If I were stumbling around drunk in the street and singing the Soviet Lithuanian anthem at the top of my lungs, or pulling a cat around by its tails or even trying to swipe a side window from someone else’s car, I wouldn’t attract as much attention from the locals as I do by quietly walking down streets while photographing old buildings. There is distrust, questioning glances, angry remarks. I’ve learned to not talk about what I’m doing because people are afraid to talk on Jewish topics. I believe that they subconsciously feel guilt for what happened. What should they hide, which generation of their family now lives in a house formerly owned by a Jew? There are quite a few who still drink their tea from a cup found on the premises or stir sugar into it with a silver spoon that had been exchanged by a Jewish neighbor for a loaf of bread.

Others are very chatty. You don’t need to ask anything. They will tell you everything, show you around, introduce you to everyone. If I have the time or an inclination for conversation, these people make my trips happier ones and add color to my impressions. Occasionally, they help to markedly shorten my searches. For instance, I would have been hard pressed to find the Babtai Jewish cemetery on my own without the help of a local man sitting near a shopping center who even accompanied me there.

In Pašvitinis, local men accurately showed me the direction in which to go and the landmarks to follow and so, 10 minutes before sundown, I was able to find the cemetery. When the sun goes down, just as during the Sabbath, Jewish cemeteries are not visited.

Adventures

There are always adventures when you travel – even in a nice, small and safe place like Lithuania. I don’t consider it an adventure if it takes a few hours to find a location that is only a kilometer away or if I need a machete to chop my way through to a cemetery or when I can’t turn around in a forest and I have to drive two kilometers backwards. An adventure for me is when the driver of a bus forgets to let me out at my stop and only realizes it five kilometers later and then I have to walk back which leaves me only an hour to visit a place that I had planned to spend two. Or when you get to the train station, only to see the last train pulling out and it’s dark and all of the hotel rooms in town are full. I had an adventure when the only way to a location was to pass through a dairy farm because the actual paths were so sunken that walking across cow manure was the lesser of two evils. It was quite a surprise to find a stranger’s clothes and a bag full of recyclable bottles in my hotel room and in another to find a cat laying on the bed in my assigned room (and after that feeling that I had made a big mistake by chasing it out because the mice in the room were extremely active that night). It was memorable when a giant flock of pigeons flew off of the beams of the ceiling when I stepped through the doors of a huge synagogue. I was very frightened when I was in the forest next to the town of Pravieniškės where Jews once resided but is now known mostly for its jails. I was nearing the Holocaust cemetery when a suspicious looking Audi with darkened windows pulled up and parked right next to my car. A skin headed young man in a gym suit got out and started following me at a brisk pace. It turned out that he was a part-time caretaker for the cemeteries and he was simply interested in what I was doing there.

Significance

You’re probably wondering why I travel in this manner. The answer is simple – I find it interesting. I know that I won’t be able to travel around the entire world, but I do know that I will be able to travel through all of Jewish Lithuania. After visiting one town, I understood that I needed to see three more. I’m also sorry that a huge part of my country’s history has been forgotten and these trips help me to remember and to remind others. I want to honor the memory of my own great-grandmother Elena, who, it turned out, was also Jewish.

I don’t hide the stories that I find; I write them down, I tell them, I share them with readers and tourists. I drove the aforementioned Chaim Mordechai’s daughter to her father’s hometown of Pilviškiai. I showed her the river where he went swimming when he was a child and the station where he got on a train that took him to a port from which he set sail to his new life in America. I know that this trip turned the lives of my fellow traveller and her student daughters upside down. They now divide periods of time into two parts: “up until” and “after” and that provides me with a great inner joy and the encouragement to continue what I have been doing.

What can be more significant or hold more meaning than to provide a foundation for a stranger who has not felt one under his feet for his entire life and to also let him feel that someone knows his family even better than he does himself.

Aušra Mikulskienė