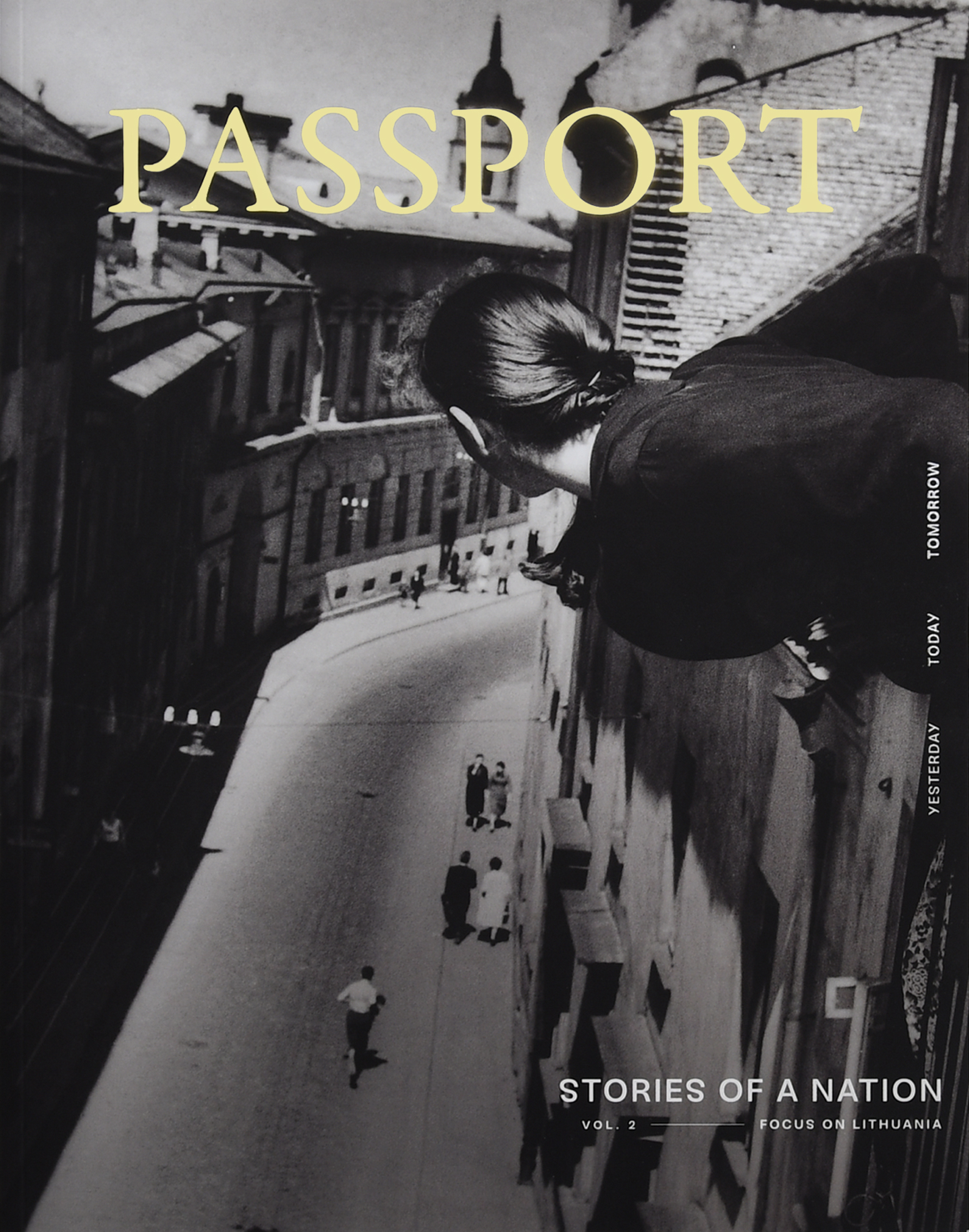

Donatas Puslys

Publicist

Photo credit: Romualdas Rakauskas

A kitchen in a soviet communal apartment, once aptly termed a human sty, with all its usual attributes: a fridge, a stove, a miniature Šilelis television set, a VEF radio and the standard kitchen cabinets. Everything everybody else has. A table sits by the wall, decked with a red-and-white checked plastic tablecloth. Set on the table are several cups, a chessboard and – at last, something unexpected – a woman with an angel’s wings, broken chains in one hand and a flag held high in the other. This is Juozas Zikaras’ ‘Freedom’, a sculpture created in 1921, embodying Lithuanian independence.

Not giving to Caesar was not an option, for this would have meant that your work would forever be confined to the drawers of your desk.

Donatas Puslys

The only question that remained was how to give him as little as possible and focus your efforts on where your will wanted to go. Attempting to locate where this line between the permissible and the forbidden lay was a task at the forefront of daily life for many in occupied Lithuania.

In 1950, Antanas Sniečkus, also known as Lithuania’s Stalin, declared that “many cities still harbour monuments erected back in Lithuania’s bourgeois past which have nothing to do with Lithuanian history or folk culture and go against the soviet regime and its people”. With these words, Vilnius saw its Three Crosses, sculpted by Antanas Vivulskis, blown up and the three saintly sculptures that once graced the roof of the cathedral disappear. ‘Freedom’ also disappeared, from the courtyard of a military museum in Kaunas, and was replaced with the bust of a soviet-era personality by the name of Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas.

As the totalitarian state seeped into all quarters of life, people did their best to find small islands of freedom – even if it was in their kitchens – and keep the flame of free thought and speech alive. As a side note, Zikaras’ Freedom survived the occupation hidden in the archives.

‘Freedom’ locked in a Soviet kitchen is a scene created by the Japanese artist Tatzu Nishi for the Kaunas Biennial. The installation is an invitation to contemplate the soviet period and our relationship to it. Another project by Nishi, also created for the biennial, transports the onlooker to a claustrophobic one-room apartment completely occupied by a gigantic statue of Lenin.

Taken together, these two pieces of installation art are an accurate reflection of the soviet times and speak of the decision faced by all who experienced it – surrender to the creep of the totalitarian state in the private domain and allow it to occupy your space, or try to push Lenin out of your living room in order to win back a few square metres to breathe freely.

Photo credit: Romualdas Požerskis

In 1972, author and screenwriter Icchok Mer emigrated from soviet Lithuania to Israel. He found it hard to come to terms with how wrong the regime was in putting his novel Striptease through the ideological meat grinder. Even in his previous work with screenplays he had encountered on many occasions that any effort to speak about the relevant issues of the day was deemed by censors to be ‘putting a stain on reality’.

As Vytautas Žalakevičius, director of the 1966 film Nobody Wanted to Die, later put it, “We rendered unto Caesar what was Caesar’s, but we also gave to God what was God’s. I was very nervous about this unfortunate nod to Caesar even as I made the film. I tried to walk the line that separated what was allowed and what wasn’t”.

Not giving to Caesar was not an option, for this would have meant that your work would forever be confined to the drawers of your desk. The only question that remained was how to give him as little as possible and focus your efforts on where your will wanted to go. Attempting to locate where this line between the permissible and the forbidden lay was a task at the forefront of daily life for many in occupied Lithuania.

Photo credit: Romualdas Rakauskas

Having become the leader of what was then the underground Communist Party of Lithuania back in the 1920s, Comrade Matas, i.e., Antanas Sniečkus, held on to his position up until his death in 1974. Lithuania’s Stalin, responsible for the exile of his compatriots, the mass murder of freedom fighters and the desecration of Lithuanian identity, outlived the real Stalin. Political analyst Aleksandras Štromas, who having survived the tragedy of the Holocaust was given refuge in the home of Sniečkus, emphasised that not only had he been a fantastic communist and committed ideologue, he was also a pragmatic farmer from Suvalkija* who wished to be master in his own country as on his own farm.

*One of five cultural regions of Lithuania

This might explain why after having destroyed monuments to Lithuanian independence he one day decided to build the Castle of Trakai*, and having been an active tool in Stalin’s russification, he later dared to disregard the whims of other soviet leaders. This is precisely why the periods of thawing and stagnation so common in the life of the Soviet Union did not correspond to those of ‘master’ Sniečkus’ (as he was generally called) soviet Lithuania.

*A gothic castle built by Lithuanian grand dukes Kęstutis and Vytautas in the 14th century. Though destroyed by subsequent wars, it continued to serve as an important symbol of national identity throughout the history of the country.

It is commonly accepted that the Soviet Union began to thaw with Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin’s personality cult in a now famous speech. In soviet Lithuania, de-stalinisation was not as rapid because Sniečkus himself was a most ardent follower of Stalin. The year 1964, when Khrushchev was removed and replaced by Leonid Brezhnev, and 1968, which brought on the Prague Spring, are considered to be the years that ushered in the Soviet Union’s period of stagnation.

However, in Lithuania it was 1972 that marked a period of stagnation. Let us take a closer look at this year.

Donatas Puslys

It was in this year that Romas Kalanta burned himself alive in the garden of the Kaunas Musical Theatre, leaving behind a poignant accusation: “Blame only the regime for my death”. This event could be viewed as a turning point. “They fenced in our land and came up with the most ridiculous laws to make life harder, and I can’t imagine that anything could ever change, even in the distant future… […] There won’t ever be freedom here. Even the word ‘freedom’ has been banned,’ Kalanta wrote in his diary.

His self-immolation and the regime’s efforts to prevent the public from participating in his funeral as well as its official smear campaign against him gave rise to mass protests in Kaunas where young people called for their forbidden freedom.

That same year marked the emergence of the first issue of the Chronicles of the Catholic Church. Three years later, prosecuted for her role in distributing the publication – which informed readers about violations of religious rights –Nijolė Sadūnaitė declared in court: “Because evil does not appreciate its own ugliness, it is disgusted by its reflection in the mirror. This is why you hate anyone that rips this mask of lies and hypocrisy away. But this does not make the mirror any less valuable! A thief may rob a person of their money, but you take what they treasure most – fidelity to their own convictions and the possibility of passing this precious gift on to their children and the younger generation.”

In 1972, author and screenwriter Icchok Mer emigrated from soviet Lithuania to Israel. He found it hard to come to terms with how wrong the regime was in putting his novel Striptease through the ideological meat grinder.

Even in his previous work with screenplays he had encountered on many occasions that any effort to speak about the relevant issues of the day was deemed by censors to be ‘putting a stain on reality’.

Donatas Puslys

It was also in 1972 that, once the protests inspired by Kalanta had subsided, Jonas Jurašas was removed from the Kaunas Drama Theatre and his staging of Barbora Radvilaitė was banned. According to theatre critic Irena Veisaitė, Jurašas found it hard to adapt to the soviet reality and its demands because “the purpose of his theatre was to say, shout, speak, whisper, yell… the TRUTH. That had been his modus operandi. And he paid for it dearly”.

Photo credit: Romualdas Rakauskas

On the eve of 1972, at Christmas, Kęstutis Antanėlis had staged the premiere of Jesus Christ Superstar, the European rock opera, at the Institute of Art. Though the KGB agents came in late, they did their job and Antanėlis was quickly fired from the Vilnius Institute of Construction Engineering.

“I’d say that most of the rebellion was provoked not so much by the musicians or by men and women from other fields, the progressive and sensible artists and scientists who were the soviet versions of the Angry Young Men, but by the censors who hid in the executive committees of the KGB, the ministries of culture and education and Glavlit,” the composer recalled.

And, in 1972, Tomas Venclova wrote The Shield of Achilles, a poem dedicated to his friend and fellow poet Joseph Brodsky who had recently emigrated or, to be more exact, been driven out of the country by the regime. In the poem he calls the USSR an unsteady ship, which Venclova himself abandoned several years later, in 1975, having written an open letter to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Lithuania.

“Communist ideology is foreign to me and, I believe, essentially wrong. Its absolute rule has brought our country many sorrows. Information barriers and repressions are applied to those who think differently, and this is pushing society towards stagnation and the country into backwardness,” was the accusation he threw in the face of the soviet regime.

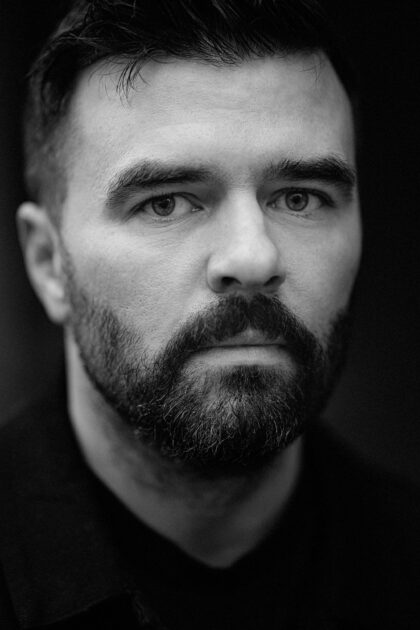

Photo credit: Antanas Sutkus

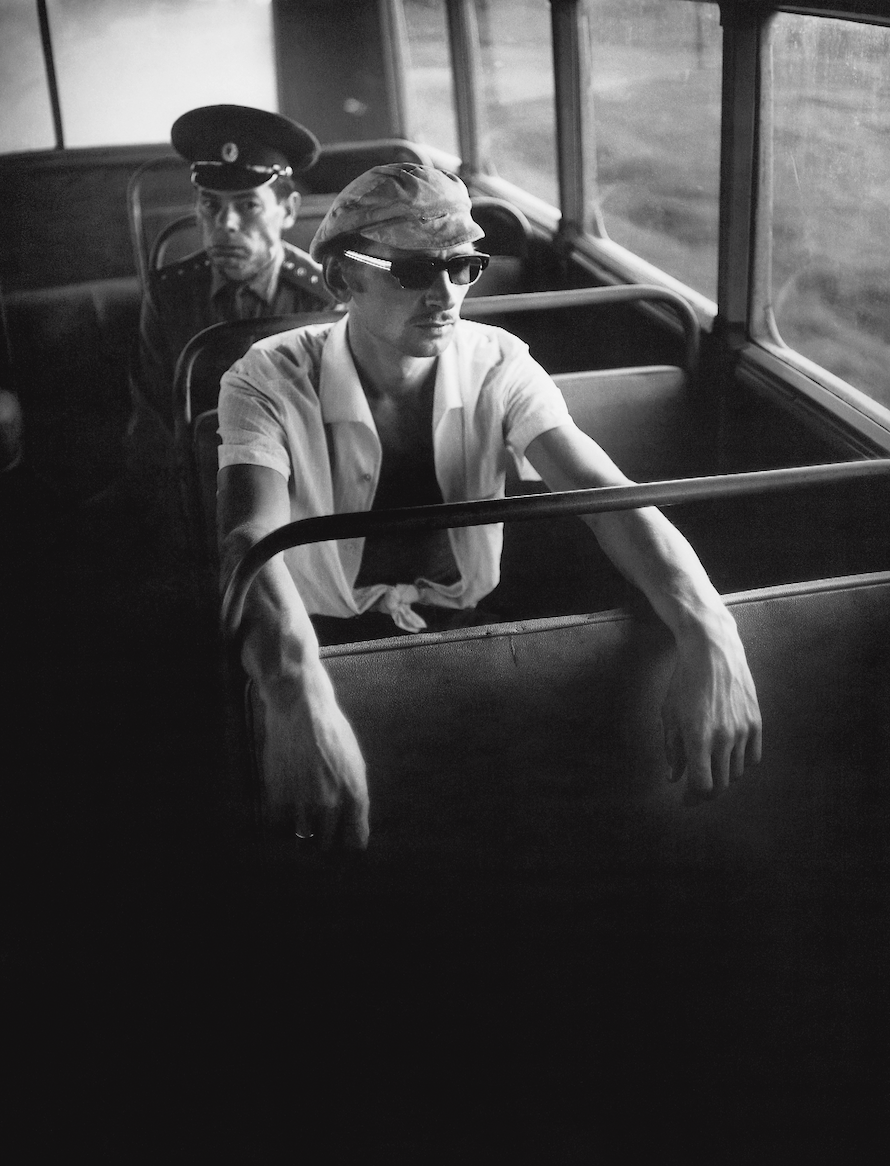

I am looking at a picture taken by Antanas Sutkus in 1972. The scene depicts two men on an intercity bus. One is wearing a white unbuttoned shirt with short sleeves, tied in a knot across his chest. With his sunglasses and a cap he exudes ease and relaxation. Maybe he’s a hippie from the Vilnius Brodas*? Or perhaps a participant of the Kaunas Spring, who once chanted, “Freedom for Lithuania” on Laisvės Avenue? Behind the man stands a uniformed militiaman whose stern features observe his every move.

*A street in central Vilnius, Gedimino Avenue, which was a popular hangout in the 1970s and 1980s among musicians, artists and young people.

It would be all too easy to oversimplify the meaning behind this picture and interpret it as a contrast between individuality and regime-instated conformity, between freedom and coercion.

Donatas Puslys

But Sutkus always looked for more than just the schematic message, generalisation or definition – he looked for the specific individual. This is why even the policeman retains his individual features.

But the monochrome picture is not neutral in its content. It points to what Žalakevičius once spoke of – the decision that falls to every man, what they will give, in light of their specific circumstances, to Caesar and what they will give to God. It’s not just black and white, it’s a conscious decision to move towards one or the other.

In The Children from the Hotel America, a film by Raimundas Banionis, there is a scene where a river long trapped under concrete finally breaks through, to Povilas Meškėla’s lyrics: “It’s not the end, it’s not the end; it’s just the long wait before a miracle”. Most of the individuals mentioned in this essay were those who gradually eroded the soviet concrete and provoked the free flow of the river. I don’t know whether they even dared to dream of the fall of the soviet prison and the approach of freedom. But certainly they wanted to live freely. To work, create, communicate and travel freely.

As described by Irena Veisaitė, they simply did not want Pavlik Morozov’s values to be the only ones to thrive in the public space while freedom was left to communal kitchens and other dark corners that escaped the prying eyes of the regime.

Donatas Puslys