Attorney

© Agnė Bekeraitytė

I identify myself as a Litvak, and as an American Jew from Maryland whose ancestors lived in and were an integral part of Lithuanian society.

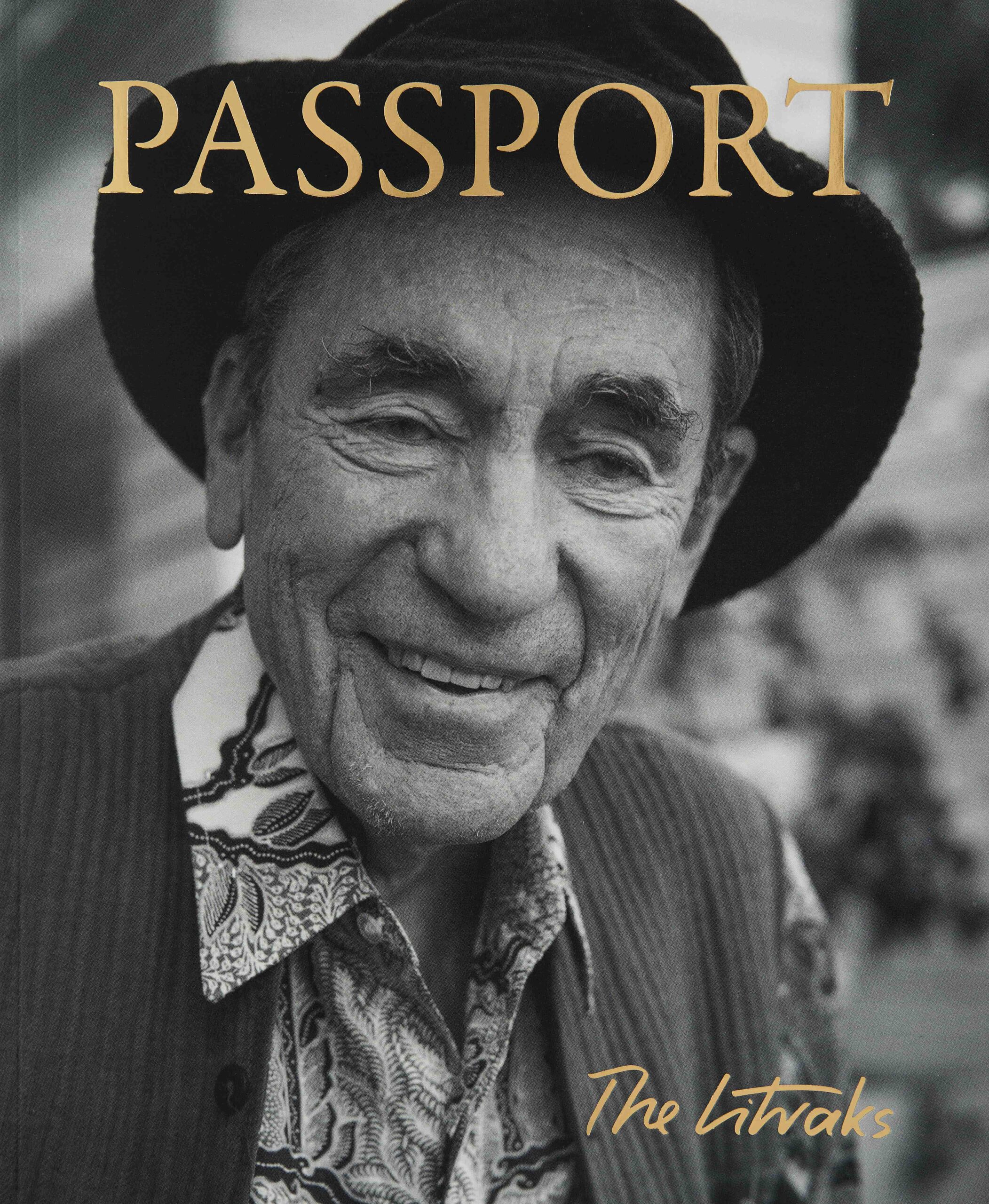

Philip Shapiro

WHEN HISTORY DRIVES THE FUTURE

For this interview with attorney PHILIP SHAPIRO to happen, we decided to take a road trip from Vilnius to the areas surrounding Rokiškis, places where his ancestors once lived. I took not only a passenger seat but also a listener’s role. Even though Phil was born in the US, it was incredible to learn how one could have such a close bond with a land and its history and the desire to make further connections.

The first question goes back to the late czarist era. Both your grandparents were born in Lithuania. Can you reflect on the story of your family in greater detail? What lessons can be learned from their stories and experiences?

All four of my grandparents were Litvaks. Three were born in the Kovna Gubernya, the province of the Russian Empire that today comprises most of the Republic of Lithuania. My maternal grandmother was born in the north-eastern corner of what was the Grodna Gubernya, just south of Lida, in what today is Belarus.

All of their ancestors were Litvaks. My Shapiro-Romm-Krok ancestors lived within 30 kilometres of Kamai/Kamajai, with the earliest known ancestor living as early as 1800 in Čelkiai, a tiny hamlet southeast of Rokiškis. My Kramer-Gann ancestors lived in Raguva and Panevėžys in 1860-1910, and the Lithuanian archives indicate that previous generations of the Kramer family had lived in Vabalninkas.

My ancestors primarily emigrated because of extreme poverty. Increasing poverty drove both Jews and Christians out of Lithuania in the late czarist era. In the second half of the 19th century, industrialization was slow to come to Kovna and adjacent provinces while the population was increasing. The employment opportunities created by industrialization in Russia proper were not available to Lithuanian Jews, who were confined to live in the Pale of Settlement, the portion of the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania that Russia annexed in 1795. Changes made by the authorities with respect to minorities following the 1881 assassination of Czar Alexander II also drove many to want to leave. During the period 1881-1914, the border between the Russian and German empires was rather porous, and there were well-established networks to smuggle people out to nearby East Prussia.

In 1901, my ancestors from the Rokiškis and Kupiškis rajonai who had arrived in Baltimore formed a mutual-assistance group called the B’nai Abraham and Yehuda Laib Family Society. This group raised money to bring more relatives out of Lithuania and get them started in their new lives. The organization still exists today, 120 years later. The relatives who left Lithuania before World War I primarily went to Baltimore, but some went to Turkish-controlled Palestine and South Africa. One of my great-grandfathers and two of his relatives went to South Africa around 1900 but he returned to Kamai and later came to Baltimore.

There were many challenges to moving from a small shtetl to a large American port city such as Baltimore. But they adapted as best they could.

How important is the story of your ancestors to you and do you talk to your kids about it? Do they embrace it the same way as you do? Why is it so important to preserve history for future generations?

I find that in most countries and most cultures, ancestral heritage is something children often don’t appreciate. It’s only as one gets older that people begin to regret that they didn’t ask questions of older generations. It is this way with my children, my wife Aldona’s children, and the children of most people I know.

In the movie Everything Is Illuminated, a young American Jewish man goes to Ukraine to find someone in the village of “Trachimbrod”, which his grandfather left just before the Nazi invasion in 1941. He is a person, who, unlike his peers, likes to collect things. As they get closer to the village, which was utterly destroyed by the Germans, his guide stops the car and tells the American and his interpreter to speak to a woman in house surrounded by sunflowers and ask her how to get to Trachimbrod. She tells them, “You are here. I am Trachimbrod.” When they go into her house, they see it is filled with random artifacts from the destroyed village. They ask her why she collected and keeps these things. She answers, “In case. In case someone comes looking.”

Aldona and I work on projects that will enable people in the future to find details about the Jewish communities in Lithuania (and Belarus) “in case … someone comes looking.”

How would you describe your cultural identity and ethnicity? Do you identify yourself as a Litvak? What does it mean to you?

I identify myself as a Litvak, and as an American Jew from Maryland whose ancestors lived in and were an integral part of Lithuanian society. It depends on the relevant frame of reference, just as my wife Aldona is known, alternatively, as an Anykštėnė, an aukštaitė, lietuvė or European. In each context one will see differences that can divide people or similarities that can bring people together. Our initial impulse is to identify what we have in common with others.

My ancestors were not pushed away. In the period 1881 to 1915, there was no Republic of Lithuania. Lithuanians, Belarusians, Poles, and Jews were minorities under the control of czarist Russia, which tried numerous tactics to transform them into Russian-speaking Russian Orthodox subjects.

Philip Shapiro

Before this interview, together we visited a few places in Lithuania, including Rokiškis. You were deeply attached to all of those places, even though you were born in the US. How can one be so attached to a land that pushed his family away?

My ancestors were not pushed away. In the period 1881 to 1915, there was no Republic of Lithuania. Lithuanians, Belarusians, Poles, and Jews were minorities under the control of czarist Russia, which tried numerous tactics to transform them into Russian-speaking Russian Orthodox subjects. It was the Russian authorities that banned any use of the Polish language and permitted Lithuanian to be written only in Cyrillic letters.

During this period, the Russians occasionally tried to incite Christians to conduct riots – pogroms – against their Jewish neighbours. In nearly every instance the Lithuanians refused – they viewed the Jews as a fellow oppressed people. There were many ways in which the two peoples cooperated with each other. All of my family’s memories of Lithuania were of poverty, but not of hardship caused by Lithuanians.

I have been a lifelong member of my family society, formed in 1901 by people who had lived in the regions of Rokiškis and Kupiškis. These places, like Kamajai, Pandėlys, Panevėžys, Raguva and other places where my ancestors lived, have always been part of my emotional attachment to Lithuania.

Would it be fair to say that you grew up in a traditional Jewish household? What was your experience growing up?

Yes. My family was a typical American family that practiced Conservative Judaism at home and attended an Orthodox synagogue, which was quite common in Baltimore. Friday evening dinners and Shabbos/Sabbath lunches after synagogue services were always time reserved for my family to spend together for conversations and discussions without any distractions.

I attended a Jewish parochial school from grades 1 to 6, and it was based on the “Lithuanian” model of teaching, which followed the Vilna Ga’on’s admonition to learn the sciences as well as Jewish studies. I also grew up knowing my extended families on my mother’s and father’s sides.

What were your expectations of Lithuania before coming here for the first time and the experiences you left with?

I first came to Lithuania in 1997 with my brother David, who is an attorney in Baltimore. He had the same upbringing that I did. Each of us had tried to visit Lithuania since the early 1970s, but the Soviets would not allow it. In 1971, I and two fellow university students received visas to drive on a specific route from the Soviet-Finnish border to Leningrad, Moscow, and Kiev, and to exit at the Ukrainian-Polish border. This gave me some understanding of what life must have been like in Soviet Lithuania – even though we couldn’t get anywhere near Lithuania.

During the 1971 visit, we were able to visit Babi Yar. In the West, we knew Yevtushenko’s 1961 poem by heart. And we were witness to the truth about the Soviets’ political distortion of the history of the Holocaust. There was no monument to actual victims, only a memorial plaque noting that “Soviet” citizens had been killed by “fascists”.

I never thought that I would have the opportunity to live in Lithuania. During the Soviet era it would have been impossible for me to travel freely in the land of my ancestors. I couldn’t have imagined that within my lifetime the Soviets’ “evil empire” would collapse.

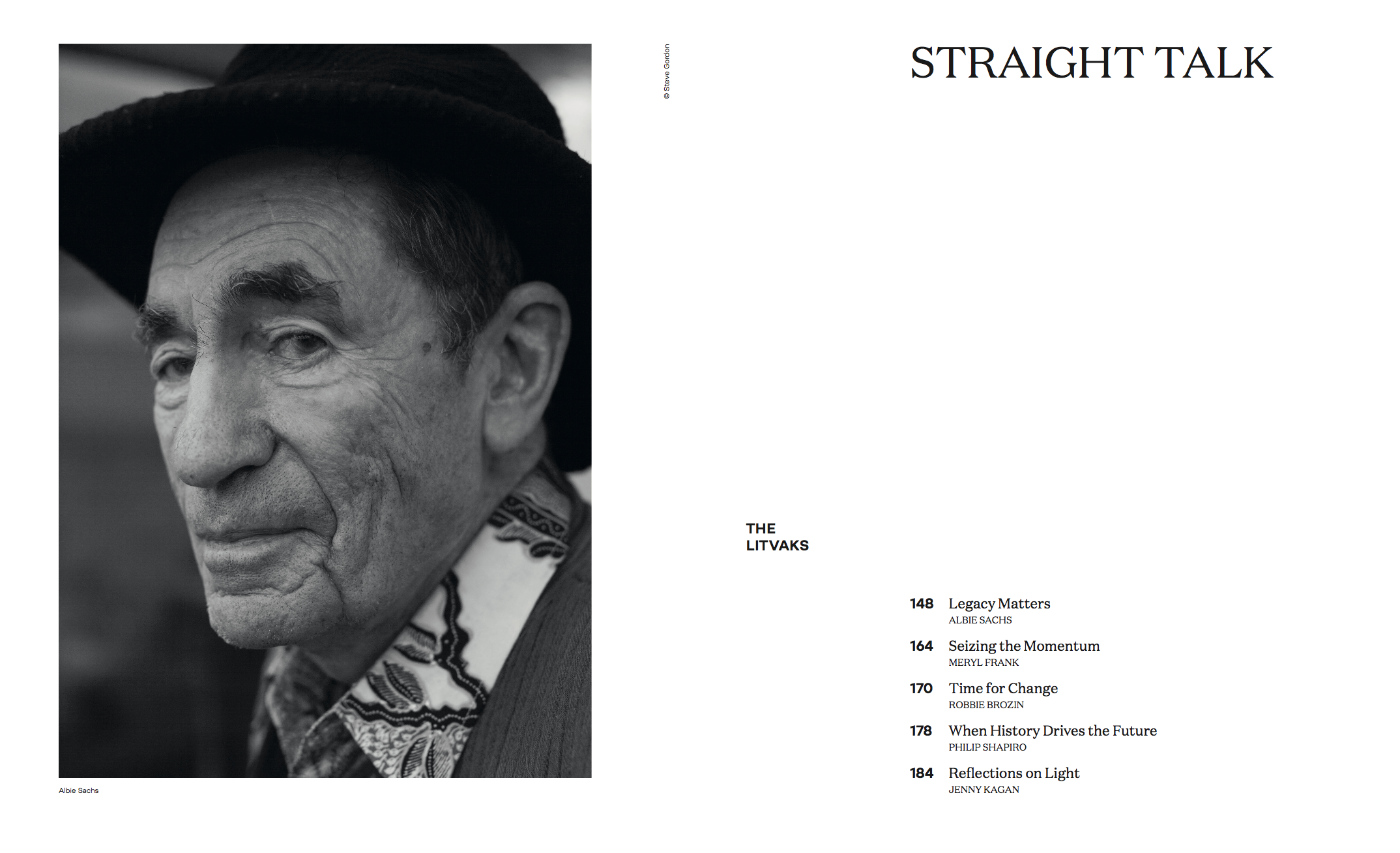

Philip Shapiro

In 1997, my brother David and I spent ten days in Lithuania. The trip was divided into three sections, with three different guides. We rented a car and set our own itinerary in a way that enabled us to go to the places we wanted to see and spend time talking to individual Lithuanians. Older Lithuanians were very anxious about encountering Jewish visitors from the West. It was said that this was because most homes in towns had belonged to Jews and that these homes were distributed to ethnic Lithuanians when the Jews were killed. While that may have been true, I think the anxiety may also have been due to the possibility that the visitors might ask about what these Lithuanians had seen in 1941. We took great pains to explain that our ancestors had left in czarist times, before World War I, and that we didn’t want to ask about 1941 and were instead interested in knowing any stories they may have heard from their grandparents about life in the czarist era.

Nonetheless, our presence triggered deep sadness among many older women. They would start to cry, remembering the specific day that their Jewish friends and families were marched past them at gunpoint on the way to the killing sites. They clearly remembered – as would anyone – the sounds from a nearby wooded area of screaming and shooting and sometimes truck horns blaring to drown out those sounds. Men spoke less. However, one man in Kupiškis told us that when the Jews were taken out of the town, he climbed up into the church belfry and was able to see what happened.

There were also a few men who said that we were “misinformed” and that no Jews had ever lived in a given town. Such comments left us with the impression that these men were deeply involved in the evil that happened in 1941, when Jews were systematically robbed of their homes, their clothes, their dignity, and their lives, and in the subsequent efforts to erase the centuries-long presence of Jews in these towns.

Younger people we met had none of this emotional weight. For them, the collapse of the Soviet Union meant that they could be in contact with the West. The Soros Fund had established and increased the availability of the internet, which accelerated the process by which Lithuanians could speak to and integrate with Western Europeans. Aldona was our guide-interpreter for one of the three segments of our 1997 visit.

Like other tourists who take “roots” trips, we wanted to walk on the streets where our ancestors once lived. Some of our ancestors lived in the hamlet of “Tzelkai” in 1800 but we couldn’t find it on any map. We asked the experts at the Rokiškio krašto muzijus where the hamlet might be and they said they had never heard of such a place. However, our guide for that segment of the trip, the legendary Regina Kopilevich, understood the pronunciation characteristics of Litvish Yiddish. She asked the experts if they had ever heard of “Čelkiai”. Immediately they recognized it. It was four kilometres southeast of where we were standing.

However, like all Western visitors, we were aware that Lithuania was a country with a dark past that it did not want to confront. The Biblical story of Cain and Abel (Genesis, 4:9-10) came to mind. Indeed, it still comes to mind.

I constantly remind myself that to communicate with someone else you must associate what you want to say with what the other person already knows, and must do it in a way that engages the listener.

Philip Shapiro

Very often, we ethnic Lithuanians choose a convenient path and take pride in or remember what inspires us – famous artists, scientists, businessmen – and turn a blind eye to less comfortable and painful truths. Why do you think this is? Is it necessary to talk about events that are still painful to remember? If so, why?

Although I have my own thoughts on the subject, this is ultimately a matter that Lithuanians must confront themselves. I do find it interesting that Lithuanians are interested in being “associated” with Litvaks who never came to Lithuania and who achieved fame in the greater world, but would not willingly accept them as fellow countrymen. This is what occurs with respect to Lithuania’s Right to Nationality certificates, which are restricted to descendants of ethnic Lithuanians who left before 1918.

To illustrate, consider a hypothetical situation in which a Jewish family and an ethnic Lithuanian family lived in 1900 in the same building in Kaunas. Each family had a 20-year-old son who were friends and in 1901 they emigrated together to Chicago. There, the boys married and had generations of descendants. One grandson of the Jewish emigrant achieves fame as a songwriter and a monument is erected in Lithuania to honour his “Lithuanian roots”. In 2020, the songwriter and a grandson of the ethnic Lithuanian each applies for a Right to Nationality certificate, which expedites the process for one day becoming a citizen of Lithuania. The songwriter’s application will be rejected. The application of the descendant of the ethnic Lithuanian will be granted.

Is it not too late for us Lithuanians to build bridges with the Litvaks? If not, what steps should be taken to strengthen our ties?

I can only speak for myself. Most Litvaks around the world had family members who were murdered in 1941 or have friends whose family members were murdered. And the specific details of how each Jewish community met its end is well documented and well-known. This information is generally available on the internet but is a taboo subject in Lithuania. Indeed, there is a general perception outside Lithuania that discussing the actions of certain individuals will result in both criminal prosecution and a suit for civil damages. This perception, combined with other actions of the Lithuanian authorities, causes many to believe that Lithuania has no interest in a serious, in-depth and frank exploration of the greatest obstacle to the relations of Lithuanians and Litvaks. Accordingly, bland, ritualistic statements of “regret” made without any real understanding of what happened are seen as hollow.

By contrast, West Germans have undertaken a thorough examination of their past, identifying what harm was caused by whom, and have internalized this information. As a result, their expressions of regret are considered to be sincere. Indeed, my daughter who lives in London has a German boyfriend and the two families are quite accepting of the relationship.

In South Africa, the painful past of Apartheid was effectively addressed through a credible, neutral and unrestricted Truth and Reconciliation Commission. I don’t know if Lithuania has the courage to host such a procedure, nor do I know if it could be designed well enough to achieve the same degree of success that the South Africa process did. But I think if it was considered to be fair and impartial, a Lithuanian commission of this type could be very positive.

Any closing thoughts?

I commend the initiative of Passport Journal to devote an edition to Litvaks and their heritage. Sharing information about the common history of ethnic Lithuanians and Litvaks promotes mutual understanding.