Austė Nakienė, ethnomusicologist

Lithuanians lost their freedom during the years of occupation, but they didn’t lose hope that independence would one day be restored. Half a century was spent trying to liberate themselves from oppression. Cultural resistance united Lithuanian society, yet all of its strata understood different means for achieving the same aim. The work of resistance writers, musicians and artists stirred the young, and vice versa – the rebelliousness of youth sparked creative work. In 1972, a spontaneous youth protest against the restrictions of civic and personal freedom forced the Party to try to understand who was to blame. It was decided that it was the fault of the humanitarian Kaunas intelligentsia. The Party made reference to ideologically unacceptable articles published in the periodical Nemunas, nationalistic feelings incited by the Kaunas State Drama Theatre, and writers and playwrights who wrote too much about Lithuanian history (Aleksandravičius, Žukas, 2002, p. 61).

It’s not easy to say exactly what contemporary national and civic consciousness might be, nevertheless it is being formed in schools, fostered in families and symbolically expressed in everyday life. People’s general understanding of what it is usually breaks out at critical moments.

Austė Nakienė

These days, there is discussion about what brought us closer to independence. Was it the conservative cultural movement made up of people who preserved the cultural values of the past, who created ethnographic clubs and sang folk songs, who published The Chronicles of the Lithuanian Catholic Church? Or was it the modern movement made up of those interested in democratic values and western lifestyles, who listened to Voice of America on the radio and strummed guitars (Kavaliauskaitė et. al., 2011)? What tore at the social order more – writers using expressive metaphors and Aesopian speech to talk about freedom, or provocative appearances, that is, body language and the hippie expression of personal freedom?

Both were important. During the years of occupation, folk, literary, Christian and other traditions became secret Lithuanian social weapons that helped push back against ideological pressures. But new information also helped usher in liberation. A person could limit the influence of the soviet system by listening to foreign radio stations.

We can learn quite a bit about the music, styles and leisure time of the younger generation through the electronic books Soviet Lithuania: How We Lived, 1953-1985 (2003) and Lithuanian Rock Pioneers: 1965-1980 (2000), including the latter’s expanded later edition Lithuanian Rock Pioneers (2012), Mindaugo Peleckis’ Lithuanian Rock and others. We can study the lifestyles of the young and their modes of self-expression from various perspectives. But here, we are not interested in the musical originality or uniqueness of the rock, disco or hiphop generations that arose in Lithuania but in the values that were passed on from generation to generation, in how with every wave of a new movement in youth culture the consciousness of nation and citizenship was expressed.

THE BEGINNINGS OF LITHUANIAN ROCK

In the first decade after the war, Lithuanians felt like they were being squeezed by the giant concrete hand of Stalin’s monument. There was no talk of freedom – if you wanted to survive you had to obey the ideological party line. In the beginning of the 1960s, with the political climate slightly warming, the first café-bars appeared in the cities and you could hear jazz, bossanova and the rhythms of the twist, boogie-woogie and rock-and-roll. A little later, around 1965, the first rock groups in Lithuania started to form, called at that time big-beat groups. The city streets of the mid-sixties reflected distinct changes in fashion styles, lifestyles and modes of interaction* – the hippie movement had begun. Aleksandras Jegoras-Dyža, a member of the movement, remembers, “We felt free from our parents, from the social order.” (Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, 2012, p. 138).

“… wearing t-shirts emblazoned with the stars of sports and cabaret, wearing weathered jeans and sweaters, the young men caroused. They minced about, feeble, slack, lacking their former vivacity and determination. Women’s fashions were more hesitant, as women were confused. Look, here a mini, there a maxi, here’s a split skirt, while the older ones remained faithful to their expensive, trustworthy pleats. They showed off at resorts with pleated red, green and blue suits sewn by themselves, diligently doing their hair, while the younger ones took this and that from the boys – belts, sweaters, men’s jeans, shoes – and they took certain behaviours and bearings from them as well. And not only that, but their bodies stretched out, becoming less curvy. The decision was a compromise: both genders moved towards their opposites. Without shyness or fear they began to trust each other with secrets hidden for ages, to dissipate the old attractions and mystery; something physiological and biological swam to the surface; it became easier to get closer, easier to separate, and fewer were left bereft, unhappy, unsatisfied, curious, insulted or spiteful.” [from the novel, Highways before Dawn, Radzevičius, 1995, p. 292).

The noticeable changes thrust their way onto the popular music stage as well. Cafés with cabaret orchestras were frequented by reasonably well-off engineers and representatives of the creative intelligentsia. The younger generation frequented more out-of-the-way places, such as high school and university dances. They didn’t like to see stuffy behaviour on stage – ranks of orchestra musicians with some smartly dressed singer in front of them. They weren’t interested in watching how the ‘star’ took centre stage from the wings and then pitter-pattered back behind the scenes (Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, 2012, p. 131). They wanted to cut loose a bit – let everyone run onstage together and play a favourite song, rousing the fans. “In those days, people were delighted by the Beatles’ attitude of creating things together. The possibility to write a song together with the instrumental parts was very attractive, if not intoxicating.” (Romas Lileikis, Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, 2012, p. 207).

There were not many pathways for new music to get to Lithuania, but the most important was the radio.

Austė Nakienė

Music by The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and others flew to Lithuania through the waves of the ether, making a huge impression. The stations Luxembourg Radio and Voice of America had the highest number of listeners, but they could barely be heard due to the jamming devices in the cities. You had to sit by the radio all night to hear your favourite song (Soviet Lithuania, 2003). People searched for other information with equal patience; you could find out this and that about rock groups by reading Polish and Czech journal columns with miscellaneous entries, and you might catch a bit of a concert by watching The Fall of Capitalist Society cinema newsreels. Vytautas Kernagis, one of the rock pioneers, said he would go to the cinema several times over to catch those clips (Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, 2000). Some people were able to get records from the West, sent by émigré relatives abroad. Such records were illegally copied onto cassette tapes and were even reproduced using a rather strange medium, old X-rays (Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, 2012, p. 154).

On hearing one or another group, the young became enamoured with the sound of electric guitars, rock bands being made up of lead, rhythm and bass guitars. Electric guitars were jerry-rigged from Russian acoustic guitars, or made from scratch. For amplification they would use sound systems from cinema halls. If they couldn’t get their hands on those, they would just make amplifiers from scratch. “What you made is what you had. No amplifiers. Microphones you got where you could, giving a bottle to some alcoholic film studio worker. There were no power cords. […] We were famous in Lithuania for a long time because we had the only neon sign for our name, Vacuum, which we would hang over the stage. I would steal the bulbs myself from old store signs thrown out with the rubbish. I also found transformers by the garbage of a grocery store on Vokiečių Street. In other words you had to make everything with your own hands from beginning to end.” (Norvidas Birulis, Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, 2012, p. 43).

It would also happen that, during rehearsals, they would spend more time setting up the electronic system than actually playing.

Austė Nakienė

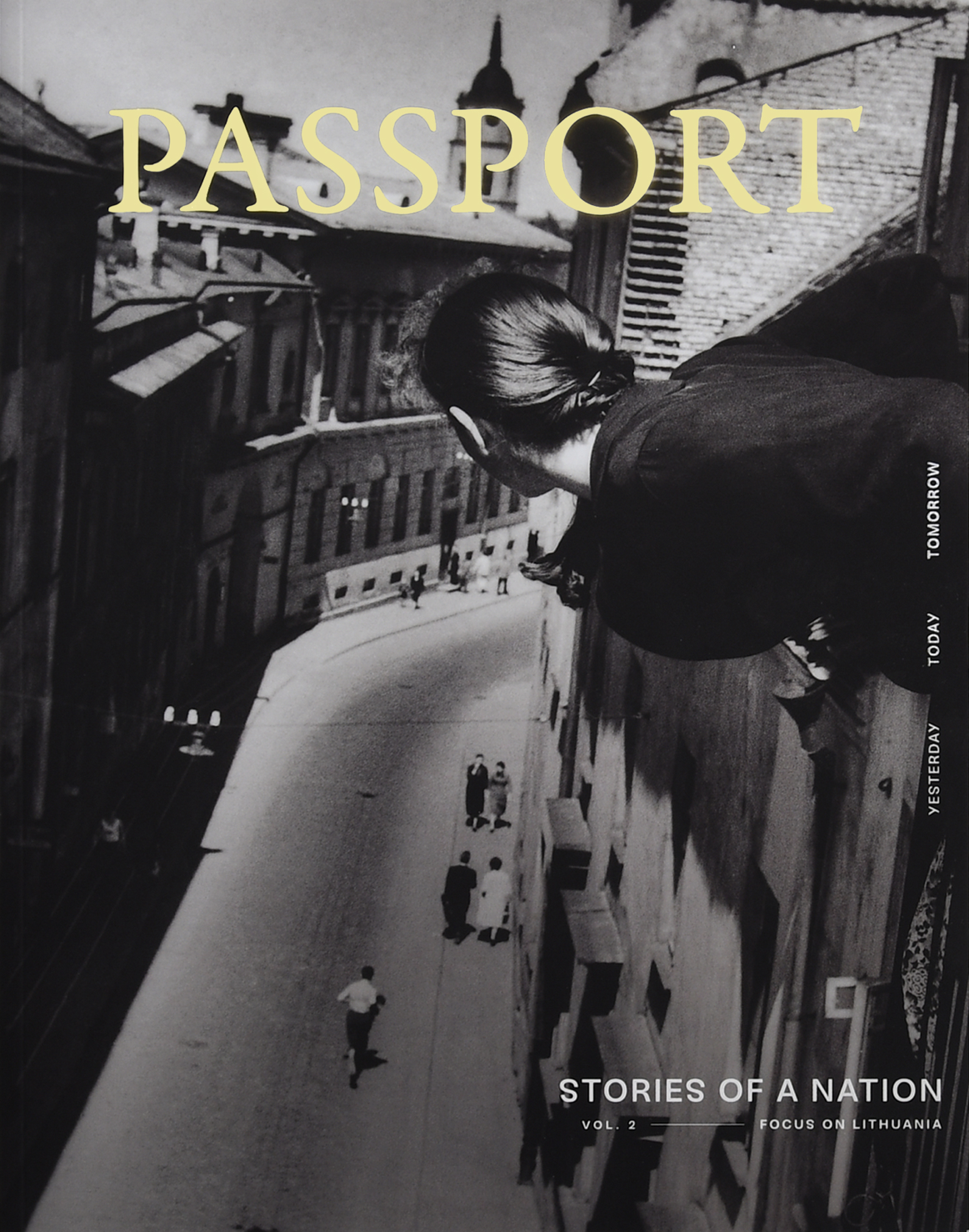

Jeans would be sent by relatives in America, while other clothes and accessories would be sewn by hand. The lyrics were open, the music simple, the arrangements distinctive, the recordings amateur. Photos of the bands would rarely be taken in studios or on stage but in natural settings or in the Old Town. In several band photos you can even see the remains of castles (Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, 2000). The symbolic value of this is easy to explain – in romantic Lithuanian poetry ruined castles symbolize the loss of statehood. Not one Lithuanian wanted to accept this fact.

In conversations with rock pioneers you often hear the word “lift”, that is, to play a song by ear. Not only music but lyrics were replayed in this way because no one knew English well. Sometimes songs were played twice – once in English, then in Lithuanian. The song “House of the Rising Sun” by the especially favoured band The Animals was given words based on the poetry of the national rebirth poet Maironis: “With mould and lichen grown high, behold the venerable castle of Trakai.” According to contemporaries, the words were adapted by Kernagis (Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, 2012, p. 165).

The editor of Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, Rokas Radzevičius, writes:

A romantic gaze into the past and the search for eternal, primordial values are inalienable components of rock culture throughout the world. America rediscovered Native American culture, shamanism, ancient Indian religions, while young Lithuanians looked, perhaps subconsciously, for a point of departure in its country’s glorious history, folklore and generally in the original culture. This was reflected in the names of the bands: Aesti, Elders, Clover, Flower Children, Whole-Grain, Iron Wolf, Children of the Sun, Amber Beads, Merchants, Descendants of the Thunder God, Bards, Flowers, Sorcerers, Bees, Firs, Pixies, Breaches, Grasshoppers, Jays, Monks, Lipshavers, etc. (Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, 2012, p. 446).

Photo by Vydmantas Juronis, circa 1969

Band names were like passwords. Only the musicians and fans called the bands Elders and Aesti by name. In official promotional materials it was merely stated that a concert would occur with musical and vocal ensembles from such and such a school. Why was Internal Security so scared of these names? Was it not because they were similar to the nicknames of Lithuanian writers from the times when the Lithuanian press was outlawed, or to the partisans who fought in the forests after the war: Lightning, Sprout, Hawk, Whirlwind, Poplar, Birch? They probably feared that the 60s rock movement would remind people too much of the earlier national liberation movements.

Photo by Vydmantas Juronis, circa 1969

It’s interesting that in the repertoires of the first rock bands there were quite a few folk songs. This is witnessed by electric rock encyclopaedias and a compact disc released in 2013, where to the accompaniment of guitars certain folk songs were sung: “Oh, rue, rue”, “O what gardens and gardens”, “Think about it, little duck”, “The bright sun rises, rises”, “When I was little”, “I’ll come my baby, I’ll come” and others. These songs connected the get-togethers where rock music was played with the evenings of folkloric dancing for the young. The aging songs, slowly going out of style, were refreshed for listeners by contemporary renderings with more intense sound combinations. The rock pioneer Arūnas Navakas was probably right in saying, “Rock music is essentially a kind of folk music, in other words a living tradition.” (Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, 2012, p. 233).

Photo by Rimvydas Strikauskas, 1973

THE FIRST LITHUANIAN MUSICAL

The first Lithuanian rock opera or musical was also connected to folklore, with tales, legends, witchcraft and spells. In 1970, the talented rock musician Kęstutis Antanėlis received from a friend the newly released record of Andrew Lloyd Weber’s rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar. He was so enamoured of it that he decided to perform the piece. By merely listening to it he was able to write a score for almost the entire opera. On December 25, 1971, Jesus Christ Superstar was performed in the hall of the Art Academy. According to witnesses, they performed the entire piece complete with decorations, lighting, costumes and acting. Voice of America noted this performance (the first in Europe). Internal Security also took an interest in it. For putting on a religious opera that was inconsistent with the required atheistic worldview for students, Antanėlis was kicked out of higher education (Lithuanian Rock Pioneers, 2000).

Photo by Rimvydas Strikauskas, 1973

In 1972-73, the composer Viačeslavas Ganelinas wrote the first Lithuanian musical, Velnio nuotaka [Devil’s Bride]. In 1974, the director Arūnas Žebriūnas created a film version. This musical could be seen as a subversion of Jesus Christ Superstar. The prologue is set in heaven – the angels rebel and their punishment is exile on earth as devils. Subsequently, it follows the plot of a folktale – a human promises his daughter to a devil, and when the girl grows up the devil begins to pursue her, while the father tries as hard as possible to break his promise.

The music of Devil’s Bride calls to mind that of Superstar. The restless devil’s speedy speech is similar to the constantly antagonistic speech of Judas, the beautiful Jurga’s singing is similar to Mary Magdalene’s love songs, while the father’s lament drenched in guilt and asking for heaven’s grace is similar to Jesus’s monologue on the Mount of Olives. But you can’t fail to notice the originality – a plot drawn from folktales and folkloric magic, the poetically stylized songs and the country-style musical interludes, all giving the piece a strong Lithuanian character.

The experience of the persecuted characters, always feeling like someone is following them, and the understanding that their wishes were not going to be allowed fulfilment, accurately reflected the conditions of people’s lives under soviet oppression. As the librettist and poet Sigitas Geda, wrote, the musical invites you to consider the price of happiness and the results of making bargains with the devil.

Austė Nakienė

This musical was not forbidden; the censors deemed it acceptable. Nevertheless, its subtext was well understood. The experience of the persecuted characters, always feeling like someone is following them, and the understanding that their wishes were not going to be allowed fulfilment, accurately reflected the conditions of people’s lives under soviet oppression. As the librettist and poet Sigitas Geda, wrote, the musical invites you to consider the price of happiness and the results of making bargains with the devil (Ganelinas, 2000).

The rock movement culminated with a tragic event in 1972. Having left the note “The social system is solely to blame for my death”, Romas Kalanta immolated himself in Kaunas. He performed this act on Freedom Boulevard, whose name in the years of occupation reminded everyone of the loss of state sovereignty. People brought flowers to the place of his death and crowds swarmed to his funeral. Those gathered there chanted various slogans that expressed for the first time their true feelings, such as “Freedom for the young!” and “Freedom for Lithuania!”, which were most unacceptable to the government (Aleksandravičius, Žukas, 2002, pp. 33, 109).

Unfortunately, these disturbances did not change the system. Just the opposite. Afterwards, freedom for the young was even more restricted. In order to avoid the censors, there arose two distinctive directions for rock music: poetic rock, in which nothing was openly said (Marijus Šnaras’ group went in this direction), and instrumental rock, in which there weren’t any lyrics at all (exemplified by the famous 70s group, Saulės laikrodis [Sundial]). More penetrating lyrics only appeared when Mikhail Gorbachev came into office and ushered in perestroika, when there was less effort to limit the information that was made public.

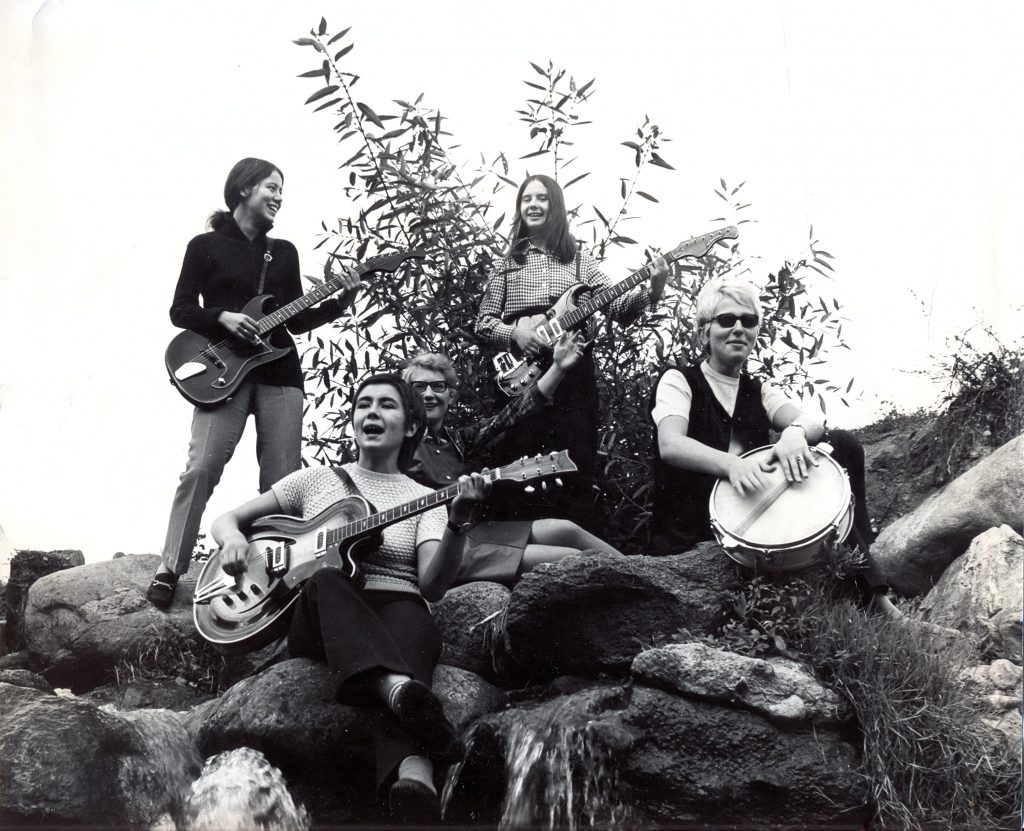

Photo by Zinas Kazėnas, 1988

THE SINGING REVOLUTION

The most distinctive band during the time of perestroika was Antis (Duck), who shook off the dominant melancholy of the period of stagnation and armed themselves with an all-pervading irony. In original songs combining rock with other musical styles, Antis poked fun at the empire’s rot, corruption and bureaucracy. A Rock March organized in 1987 clearly warned the party functionaries sitting in government seats that their days were numbered. When in 1988 the Lithuanian restructuring movement Sąjūdis was formed, the frontman of Antis, Algirdas Kaušpėdas, became a participant. Then, in the second Rock March through Lithuania*, he encouraged young people through song and speech to support the political goals set out by Sąjūdis.

Folk songs were heard during the Rock March through Lithuania of 1988. Rytis Ambrazevičius, a member of the folklore movement, remembers how together with Žemyna Trinkūnaitė they called themselves the folklore group Namo (Homewards) and participated in all the Rock March concerts: “It always began with us. That was fitting because the times were very folky-national and that kind of music fit. The first song was all acoustic, with no recording. With Žemyna we sang and played the kanklės (zither), performing a martial song that everyone knew: “All the nobles are saddling the horses, saddling the horses, riding to war.” Later, I arranged it for the ensemble Atalyjai, and you can hear it there now. The show began with the chords of the kanklės and this song… Then the other bands came on…

The atmosphere was like everywhere else in Lithuania at the time. An emotional and spiritual upsurge, flags, and on top of that it was summer. I can’t say that all the musicians themselves somehow thoroughly expressed that upsurge, but inside, I think, the majority were feeling more or less some kind of nirvana… The public probably felt positive value on two fronts – the general patriotic atmosphere of the times and, no less than that, the specific atmosphere of the concerts, having in mind that the size and style of the concerts then was something completely new.” (Ramonaitė et. al., 2015, p. 173)

The summer of 1988 saw the beginnings of the singing revolution in all three Baltic countries.

According to Guntis Šmidchens, author of The Power of Song, that year’s events in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – rock concerts, folk festivals, song festivals – saw the earlier loyalty to the greater state transform into a clearly expressed aspiration for independence. The political and resistance characteristics of the singing revolution where on clear display when the independence-era tricolour flags of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were flown above the heads of the singers (Šmidchens, 2014, p. 159). Anyone seeing the gathered crowds with a sea of tricolours fluttering above them could understand that the Baltic nations had been reborn, had got their dignity back and were ready to restore their statehood.

Photo by Zinas Kazėnas, 1988

In just a few years, all of the national and religious symbols that had been destroyed during the period of occupation were restored in Lithuania. Not only was the independence-era flag restored but the coat of arms and the national anthem too. Vilnius Cathedral and other churches were returned to the faithful, the Hill of Three Crosses monument was rebuilt, the remains of St Casimir were solemnly reinterred in their previous resting place, and the bodies of exiles were returned from Siberia and reburied with Christian ritual. The mass demonstrations that helped usher in Lithuanian independence were also characterized by religious symbolism: people gathered in squares as if in church, carrying flowers, burning candles.

Songs from the independence period are similar in sound to hymns, like gospel and soul music.

Austė Nakienė

Their most characteristic images include the day breaking after night, the earth recovering after the winter’s frost. Their most important message: the belief that justice will be restored because that is the will of the people and of the Highest. The songs often repeated the name of Lithuania or chanted the names of all three Baltic states: “Lithuania, Lithuania, you are holy to us”, “Bless us, God, the children of Lithuania, let the heavens and earth hear our voice”, “The Baltic is awakening, the Baltic is awakening: Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia!”, (a collection of these songs, Pabudomė ir kelkimės (We Awoke, Now Arise), was released by Lithuanian Radio in 2008). The philosopher Leonidas Donskis described the country seeking its freedom: “At that time, Lithuania was like a person in love who doesn’t know what time it is, doesn’t understand what is happening to him, is a bit euphoric, feeling good, wanting to see the object of his love, and repeating the same things over and over…” (How We Played the Revolution, 2011).

Photo by Zinas Kazėnas, 1988

Only one song from the time of rebirth, “Laisvė” (Freedom), based on lines by the poet Justinas Marcinkevičius, does not shine with euphoria. It considers what sacrifices independence may require and how one should behave in the eyes of history. It says to a defender of independence who doubts his courage, “Stand, stand as freedom stands.” When Lithuania declared independence in 1990, there was a desire to fully grasp it no matter what the cost. That desperate desire is expressed in the Antis song “Krantas” [Shore]. Kaušpėdas pushes his vocal chords to the maximum in order to express the immense emotional tension people had to experience while waiting for the recognition of their country and suffering under an economic blockade. Independence was truly the highest goal, “the shore onto which we piled all our hopes” (All Antis, 2003).

These days, people avoid speaking much about the boundless joy of March 11, 1990, or the painful events of January 13, 1991. People want to remember them and consider them without melancholy words. But all Lithuanians are proud of these events in their hearts. The struggle for independence did not become a war, not one Russian soldier was killed, ethnic minorities did not flee the state, and our pantheon of victims is not so very large (Martinaitis, 2004). It was a mythical victory. The feeling is well expressed by a Marijonas Mikutavičius song that later became an anthem for Lithuanian basketball fans: “We grew up on one big night. We will not lose before we are defeated.” (Mikutavičius, “Trys milionai” (Three Million)).

Photo by Vytautas Dranginis

PATRIOTIC HIPHOP

Lithuanian patriotism was also tested when it came time to join the European Union. There was a referendum for joining the EU in 2004 and posters where everywhere to be seen saying, “I love Lithuania”, “I voted”, “Let’s be Europeans”. Politicians spoke about how much we’d yet to do in order to be full members of the EU, and historians argued that we had been a part of this community since the Middle Ages. But it was not the politicians or the journalists who most accurately expressed the people’s lingering moods of hope and apprehension – it was the rappers. In the years after independence a new musical style came to Lithuania, hiphop, and a new generation arose who wanted to use this musical and lyrical style to express their views.

People were happy to join the EU and imagined a great future for themselves and their country. The majority believed that life would get better, and if not then at least there would be the chance to emigrate and make a living in another country. Yet the understanding that from now on we could go freely to almost any other European country also strengthened another dormant belief – we don’t want to leave our country! These contradictory feelings were expressed in patriotic hiphop. The strongest Lithuanian hiphop group, G&G Sindikatas (G&G Syndicate), wrote about their love for their home town in a song from the album Betono sakmės [Legends of Concrete]:

Hey Vilnius, we were begun in your underground where we learned to divide and share our words in doses… The way you made us is how you’ll have to take us. We still admire you while we smoke silently on your dark street corners, the ones not on the postcards or on the routes of tourists, cops or presidents… We’re in your flats, walls, street lamps, and you are in our arms, spirits, in the folds of our brains…

His Majesty, the Vilnius earth under my feet. I don’t regret the time I’ve given him, we are his soldiers and he needs our green blood. Even now, we attack once again! (G&G Sindikatas, “Vilnius 2002”, 2002)

This alternative musical style borrowed a characteristic feature of Lithuanian identity – the continuous wavering between the desire to free oneself and be tied down. As can be seen from the citation, the ties win out. Those who leave are the ones who can’t forget the past and feel bad in the place where they suffered wrongs. Those who remain do so because they can forget the past and love their country just the way it is.

The stronger ones remain because the others only have to adapt to a new place while those who remain have to make their place a better one.

Austė Nakienė

Hiphop texts usually liberate accumulated social tensions. Those whose opinions are ignored by the people higher up rub the truth in our faces, stunning us with the courage of their thoughts and the freedom of their speech. The ‘street level’ truth of an unrecognized generation is expressed in sophisticatedly rhymed Lithuanian texts. According to the Syndicate, “We are nameless, that’s why we’re so clamorous”. Still, this is Vilnius, not New York, and the tensions between different social classes, between different cultural and ethnic origins, are not so pronounced. Passionate poetic currents don’t carry the discord of various social groups here but rather the economic and political changes happening at breakneck speed.

After independence, Lithuanian society experienced so many new things that it was difficult to adjust to it all. After the initial free market twists and turns there was even a fear that we would not be able to withstand strong economic pressures and would become a forgotten nook in the global village. Nevertheless, we withstood it and were able to move on to new challenges. Every Lithuanian citizen understands that he or she has no inherent advantage yet has to overcome these fears and move forward, trying to win through. The Syndicate poet Svaras says:

Nobody gave me anything for the road. I never slept with success… I saw the streets fill with romantic cynics, and instead of “ours” it all became “mine”. I get it – capitalism. I saw with time the growth of ego and ambition, but I just want our traditions to be saved.

Not theirs but ours – not for them but for us – did I break myself and give you half. My half I sowed in an empty field to grow music anew that saves. Music that grows, music that hurts, music that saves… (G&G Sindikatas, “Žaibo rykštė”, 2014)

If people who usually poeticize rebellious inspiration, night-time conversations and cigarette smoke speak so beautifully about traditions then that is worthy of note. Maybe the word ‘traditions’ only showed up in the song because it rhymed with ‘ambition’, but it would be good to see this as more than happenstance, as a sense of community handed down from our parents, fostered during the times of occupation, now transformed to become a principal that guides the members of the subculture.

So the work of the Lithuanian rock and hiphop pioneers is quite authentic, and their activities are well justified. Early rock and hiphop music interestingly combines modernity with tradition, with no lack of originality or of Lithuanian qualities. Even though youth movements often maintain they reject earlier traditions and are choosing a new lifestyle and new forms of expression, national values are still handed down from one generation to another. Those 20- and 30-something rappers were expressing the same patriotic feelings in their texts as 60-something rockers.

Photo by Zinas Kazėnas, 1988

It’s not easy to say exactly what contemporary national and civic consciousness might be, but it is being formed in schools, fostered in families and symbolically expressed in everyday life. People’s general understanding of what it is usually breaks out at critical moments. As we know, it wasn’t just hippie friends who laid flowers at the spot where Romas Kalanta died but also the ordinary young people of Kaunas. And on January 13, 1991, it wasn’t just volunteer militia standing unarmed in front of the tanks but ordinary neighbourhood residents of Vilnius. Young men of contemporary subcultures also feel like they are ‘Vilnius soldiers’, faithful to their city. Time flies quickly – after a couple of decades young rebels become responsible, supportive family men and women, then another generation follows. They, too, should grow up strong and unbridled because they are reared on encouraging lyrics:

There are brave ones these days too, who won’t keep quiet, fighting the elites who only love themselves. For us, Lithuania is not a milking cow but like a sister, a brother, a father, our holy mother… What is there of your rightness if you’re not brave enough to fight, and what is there of life if you regret you were ever born? A word is nothing if it’s grey, what comes of you if you’re frail? (G&G Syndicate, “Lightning Whip”, 2014)

Both the earlier and later generations of young rebels were connected to cultural resistance. They suffered the loss of Lithuania’s statehood and believed in its rebirth. But the changing generations spoke about patriotism with different words and sang in different styles. In the mid-20th century you’d hear partisan romances and foxtrots; two decades later it was rock songs, and in the 21st century it was poetry set to hiphop rhythms seeking social justice that spoke of the Lithuanian state and our duties to it. These cultural and musical strata of the younger generations did not grow directly out of each other but appeared between the gaps, arranging themselves one after another. The turnover of poetry and music reveals how culture is built in layers. When one becomes exhausted and weak, another layer appears that bears witness to the same values with no less inspiration than that which came before.