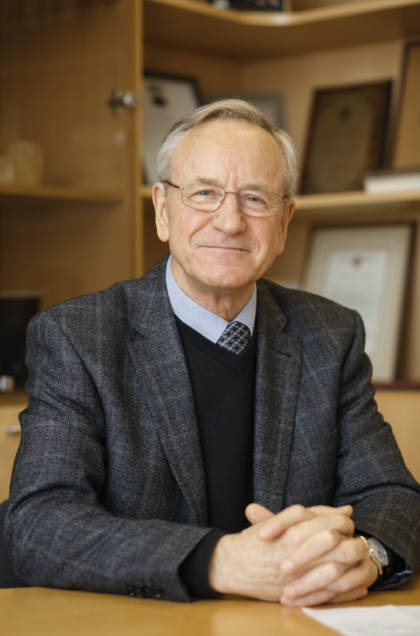

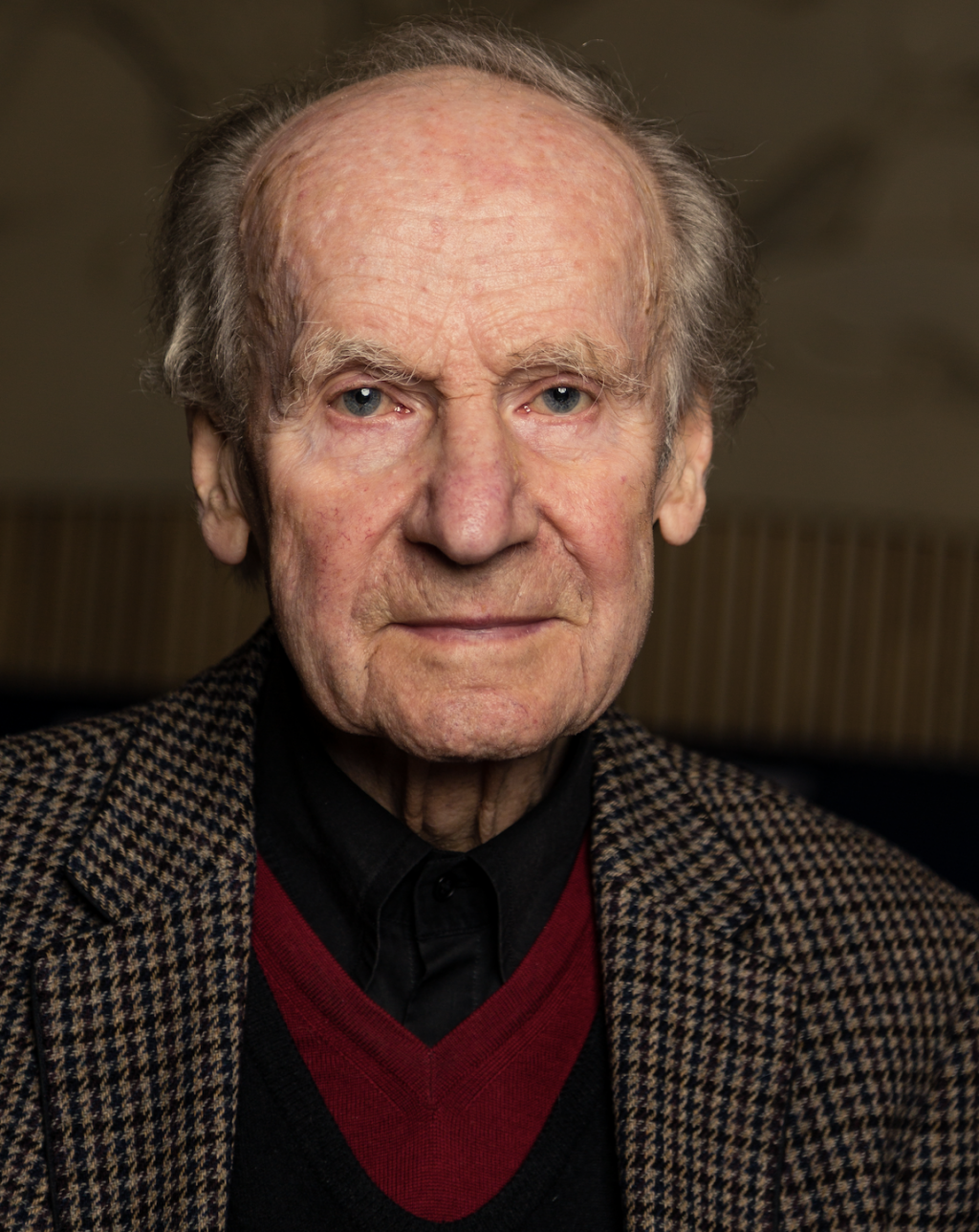

Architect, public figure (1928-2018)

FOOTPRINT ON THE LANDSCAPE

The Lithuanian National Drama Theatre, the Seimas (Parliament), the Central Post Office, the Lietuva Hotel (now part of the Radisson Blu chain), Independence Square, Baltasis (White) Bridge and the legendary Neringa Restaurant – all of these are rightfully considered symbols of Lithuania’s capital. Their architect, Algimantas Nasvytis, who designed all of these landmark buildings together with his twin brother, has also become a living symbol of Vilnius. Sadly, Algimantas Nasvytis died on 27 July 2018, shortly before which this interview was made.

Every city – whether in Lithuania or abroad – would love to have its very own architect. Vilnius is among those cities fortunate enough to have had its own dedicated designer.

I am only an architect for Vilnius. I’ve never designed anything anywhere else. This is rare, of course, but that’s just how it came to be. Perhaps it’s because I’ve essentially lived my entire life in Vilnius.

Algimantas Nasvytis

“My twin brother and I were born in Kaunas, but I’m anything but a native son of that city. I feel that I’m a true citizen of Vilnius. All the more so because very few of my contemporaries were born in Vilnius.”

Recalling his first visit to the Lithuanian capital, Algimantas Nasvytis remembers being captivated, almost obsessed, by the city. He has confessed that, even after living more than 70 years here, his enchantment has not waned. Quite the contrary – it has only grown. “Absolutely. Vilnius is intensely beautiful, and I can’t even say in what way. It’s very hard to speak about beautiful things. One can only say: it’s very beautiful. I’m convinced there is no capital city in Europe more beautiful than Vilnius. This city is more beautiful than all the others. Everything here is simply lovely, the urban landscape, every bend in the River Neris.”

Nasvytis and Vilnius are joined by an immeasurable bond that is difficult to understand, but when we listen to the architect’s stories and memories, that bond is immediately tangible. It was Vilnius that brought him to architecture – more precisely, his first trip as a ten-year-old boy to a bitterly cold Vilnius in winter.

“I understood what I wanted to be that first time after coming to Vilnius. We essentially arrived there together with the Lithuanian Army [in 1939], because my father had been appointed to the so-called Vilnius command – the Lithuanian armed forces that had marched into the capital. My father was appointed to direct the hospital at the Vilnius garrison. We arrived at night on the Berlin-Moscow train. The next morning I had my first tour of Vilnius. Because my brother was ill, my father let me walk around the city alone for three hours. He said: ‘Walk in that direction. Keep walking, and if you see something that’s not right ask a policeman.’ I started my journey at the Cathedral because I had known about it since childhood. Of course, I was incredibly amazed by the size of it. It was hard to guess its scale from photographs. My tour proceeded from Cathedral Square. I couldn’t go inside because it was closed, which is when the Three Crosses seemed to descend straight from the heavens, guiding me along the rest of my route – almost instinctively.

“Then I discovered St. Anne’s Church and the bouquet of churches around it. The Cathedral had seemed so infinitely large to me, but St. Anne’s looked so unimaginably tiny. I could’ve never have imagined it was so small. A vivid contrast unfolded before my childish eyes: the enormous Cathedral and tiny St. Anne’s. From there, I turned down the small streets of the Old Town, where one discovery after another awaited me. It was, quite simply, a path of architectural surprises: the Church of Sts. John and all of the buildings making up the Vilnius Jewish ghetto. There was such an authentic spirit there, intertwining with what no longer exists – the ghetto’s inhabitants, the Jews and their payot and fedoras. Everything pulled me deeper into the heart of the Old Town – the streets and their little arches, the intersections and the impressive silhouette of the Great Synagogue that had once struck such a strange visual resonance. Narrow streets that opened suddenly into the largest, densest section of the Old Town – Vokiečių Street and its two-storied shops.

“I got lost in the commotion of it and I no longer knew which way to go. A policeman came up to me, apparently understanding that I was not a local. I asked him to tell me how to get to the Gates of Dawn. He explained it to me so beautifully, like a tour guide would. That’s how I came across the Town Hall along the way and the mighty St. Casimir’s Church. My first mistaken impression a little further along was that I thought I’d seen the Gates of Dawn. But I began to suspect I was wrong. And, to be sure, these were not the Gates of Dawn, but the Basilian Gate. Finally, I saw what I had come to see – the Gates of Dawn. As I climbed the stairs, I found it strange to pass silver ornaments along the way: legs, arms. I couldn’t understand what these legs and arms were for and no one could explain it to me, since there was nobody else there. Only later, while walking down the stairs from the chapel, did I understand that these were symbols placed by people seeking God’s help. As I walked away from the chapel, what was especially beautiful was seeing Jews take off their hats, not to mention everyone else.

“Later, when I was older, I realised there was a connection: when the Pope arrived in Vilnius and asked to view the Gates of Dawn ensemble in greater detail, I was so impressed that he stood in the street, looking at the features of the Gates of Dawn, from the same perspective as I once had. I came to understand that we had stood on the same spot, both equal before the Gates of Dawn. Looking back on that day when I first saw Vilnius, it was that moment, when I was standing there on the street by the Gates of Dawn that the idea of architecture came to me. I realised I was obsessed. Obsessed with Vilnius. It’s as if I’d changed in those three hours. As I returned to meet my father, I felt as if I was already walking through a familiar city. Vilnius called to me just like God calls a man to the priesthood. I began to live with thoughts about Vilnius and, later, my entire life became Vilnius: its creativity and its spirit.”

Vilnius called to me just like God calls a man to the priesthood.

Algimantas Nasvytis

Nasvytis continues to be moved by the creativity and spirit of Vilnius. It couldn’t be otherwise. He helped create the face of Vilnius for more than half a century and saw the capital change and grow, becoming one of its most prominent developers and drivers of change. Nasvytis is enamoured of the Vilnius of today, but not always by its architecture.

“We have everything now. Walking through the city one can feel how its architectural palette has expanded and opportunities have grown. But with such nearly limitless possibilities, I sometimes fail to see ideas that are bold, free, unexpected and surprising. For me, there’s a lack of projects today that have been designed from the heart. We see sites in Vilnius now that already exist somewhere else. In other words, there’s a lack of authentic sincerity. Why? Several things come to mind. As paradoxical as this may sound, the influence of clients is much greater than in the Soviet period. We live more freely, but architecture is not improving as a result.

“We probably have to live for a while longer for people to begin feeling the authenticity of architectural sites – to get the impression that something has been designed with this specific place in mind, not flown in and dropped by parachute but cultivated in this particular environment. Modern architecture can exist in harmony with the old if there is a suitable place and appropriate scale for it and, of course, if everything is entrusted to the right hands. Sometimes, glass architecture is equated with good architecture but in reality – it’s like heaven and earth.”

Nasvytis also sees a paradox in the fact that, during the Soviet years of censorship, prohibitions and surveillance, the architectural profession was among the freest of careers and was essentially unfettered. “Nothing bad happened to architects. If they found their own materials for their designs, no one bothered them. It wasn’t the case that someone from on high – more precisely, from Moscow – directed a project’s artistic part. Nobody told us how things should be. The only limitation was the shortage of materials. I might be so bold as to say that, of all the artistic fields, the architectural profession was among the freest and was essentially unrestricted. During the years of liberation, meanwhile, we architects were among the first to feel the spirit of independence. In fact, architects may have had a greater sense of rebirth than others because they could see the approaching opportunities.”

Perhaps precisely because he never felt restricted or forced to design something he had no desire how to create, Nasvytis has a cautious view of Lithuanians’ drive to liberate themselves from the shackles that remind them of the Soviet period, even when they take the form of architecture or artistic legacy. The architect of Vilnius believes that Lithuanians must learn to distinguish between the ideological art of the Soviet years and the true art created in that period. Of one thing he is certain: liberation and release from a painful past comes not from the dismantling of specific sites but from one’s own state of mind, freedom and way of life.

“Without a doubt, I believe that the traces of our culture must exist and survive – the very traces that we call monuments. They are, after all, the legacy of a period when such buildings and sculptures were designed as architectural monuments. In other instances, a painting might be a monument and a sculptural work an immovable part of the cultural heritage. The debate about the sculptures on Žaliasis (Green) Bridge continues to this day: are they works of art or ideological symbols? In my view, they are perfectly fine exhibits of that period. For many people, some of what is on display at Grūtas Park [near Druskininkai, where soviet-era monuments have been put up for paying visitors] is more interesting than what has been done specifically for the bridge.”

Vilnius is full of Algimantas Nasvytis’ own footprints – some which the architect continues to follow every now and then. Very often they lead him to the Neringa Restaurant, one of the most treasured and memorable works for him personally. If you have ever been fortunate enough to be in the restaurant at the same time as its architect, he will have always been in the same place – in his most favourite spot, sitting by a small table in the very centre of the small hall, shielded from the noise of Gediminas Avenue by a broadleaf plant. While Nasvytis treasures most of his works, he says he doesn’t boast about any of them.

“I don’t like the word ‘pride’. I prefer ‘enjoy’. And I get the most joy from Neringa – that it still exists. There was a less propitious time when it could have disappeared, but fortunately it survived. I feel at home here, even if its spirit has changed somewhat. The greatest change at Neringa has been the people who frequent it. Entirely different kinds of people gather there than before. In the past, a wonderful company of so-called ‘veterans’, people who discovered the place when it first opened, would meet there – artists and intellectuals. They’re gone now. Perhaps the prices are too high and not everyone stops in anymore. Even so, there’s still quite a bit of authenticity here. Even the legendary chicken Kiev is just as delicious. In truth, I’ve never found a better one – and I’ve tasted quite a few.”

Algimantas Nasvytis is only ten years younger than the century-old restored Lithuanian state. He has seen Lithuania through various periods of time, ruled by different regimes and people – destroyed and rebuilt, occupied and free. He enjoys living in Lithuania today, seeing it grow more beautiful and modern, expanding its horizons, but he is nevertheless convinced that it’s too early to judge Lithuania’s progress – we as a country are still too young. All the more so because, in Nasvytis’ view, there are still plenty of things that need correcting in our country, especially within society.

“Perhaps it’s too early to draw conclusions. But it seems to me that there have been some very positive shifts. Things like ornamentation appear when something is missing. That’s when you need decoration – which also applies to architecture, and especially so. Lithuanians, however, are still a very modest people by nature, and it’s fine if such things are reflected in architecture. I feel that the Lithuanian spirit, our nature, is best reflected in the Old Town. It’s not overburdened and the details there are restrained.

“There are many things that need correcting in Lithuania today. And the worst thing is that they often overwhelm the positive. It’s a bit sad, perhaps, that there aren’t enough good things that we notice in our lives, which means there isn’t enough space yet for the positive. In all aspects of life, I believe the scales should tip towards the positive side. We’ve had great achievements everywhere, in science, art and sports – but perhaps not enough yet, or not enough attention has been devoted to them. I’d like there to be more of those good things or, to put it more precisely, that there be more people creating and noticing the good things.”

Raised by Kazimieras and Elena Nasvytis, Algimantas Nasvytis was encouraged to love Lithuania. His late twin brother Vytautas also chose the path of architecture. The two brothers almost always worked and designed together, sharing their love of life in Vilnius. Their older sister, Undinė Nasvytytė, was also well known throughout the country, becoming a legendary voice on Lithuanian national radio and television. Their father Kazimieras was a colonel and physician in the Lithuanian army. During the Second World War, in 1941, he was arrested, convicted and deported to Siberia. The Nasvytis family is a true example of Lithuania’s intellectual community, a living testament to their country’s most painful and beautiful experiences. Perhaps this is why, when asked what the word Lithuania means to him, his answer is succinct: “I grew up in a Lithuanian family where the word ‘Lithuania’ was always spoken in the most profound sense, and Lithuania always meant the most deeply felt things.”