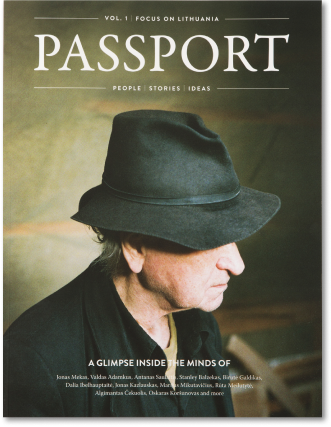

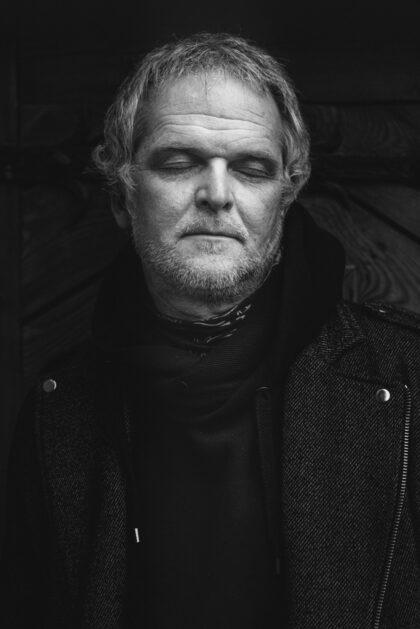

Leonidas Donskis (1962–2016)

Professor of Politics at Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas

It was not that people lost their souls and sensibilities; instead, Lithuania joined the 21st century, and the post-Communist world proved keen to change beyond recognition what was left of the old European one.

Leonidas Donskis

AN INSIGHT INTO MEDIA

A quarter-century has passed since the year 1988, which marked the beginning of the end of the former Soviet Union. Sąjūdis, the national rebirth movement of Lithuania, came into existence, blazing the trail to freedom and independence for Lithuania and other Soviet republics. Gaining the initiative, consolidating symbolic power and authority, and making people believe that the time had come to change history, world politics, and to restore justice – all these magnificent things would have been beyond reach if the Lithuanian media had not changed the public domain almost overnight.

In fact, it was a lucky combination of dedication, courage and passion that made it possible to reform and revamp the entire Lithuanian public sphere in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This was not entirely surprising; the old Soviet professionalism, deeply embedded in the abyss between specialized writing and political engagement, retreated, allowing new ways of thinking and writing to take its place. Many columnists in the early 1990s came from literature and art criticism; others were new figures in the media and press, their roots in civil and political protests brought about by Sąjūdis.

Suffice it to mention some celebrity writers who influenced and even shaped the then-leading dailies, weeklies and magazines. Such noted Lithuanian writers and essayists as Jurga Ivanauskaitė (1961-2007) and Ričardas Gavelis (1950-2002) served as columnists for the daily Respublika. Incredible as it sounds, Respublika, now notorious for its anti-semitic and homophobic editorials and slanderous writing, was once home to Jurga Ivanauskaitė’s pieces on society and culture and Ričardas Gavelis’s brilliant essays.

Later, Gavelis would begin working with the magazine Veidas, whose closing section was reserved solely for his provocative, caustic and ironic pieces. Rolandas Rastauskas, one of the most renowned essayists in Lithuania, was writing his essays exclusively for Lietuvos Rytas. All of these publications greatly benefited from the talent of the aforementioned writers.

The late Gintaras Beresnevičius (1961-2006), a cultural historian and public intellectual who was easily able to surpass any political commentator in terms of power and novelty of insight, was a true heir to the characteristically Lithuanian tradition of valuing the bright humanist capable of lending his or her talent to social analysis and political commentary. He was a true heir to Gavelis, but only for a short while. Alas, all three – Ivanauskaitė, Gavelis, and Beresnevičius – died very young.

What happened next was a swift deterioration in the level of public discourse. Pandora’s Box was opened: everybody was welcome to comment online, the debate measured by sheer commercial success. Quality of thought and expression was not an issue anymore: Lithuanian online publications allowed and even welcomed anonymous comments on or alongside serious essays and professional comments. These anonymous pearls of wisdom always were and continue to be full of anger, frustration, hatred, ad hominem attacks, overt anti-semitic remarks, homophobic insinuations, and even more frequently, personal insults, poisonous darts and toxic lies. This is the ugly face of our media, an aspect that has distorted all the good and novel things in Lithuanian online press – hard-won things that were brought about by freedom of expression and fundamental political change.

Yet, “the medium is the message.” This piece of Marshall McLuhan’s creative genius and power of anticipation strikes us as a prophetic foreshadowing of the 21st century. Idiom, form, language, political and moral sensibilities, and figures of speech, everything changed overnight. As paper dailies and magazines died, the electronic portals began to dramatically change the landscape of Lithuanian media. It was not that people lost their souls and sensibilities; instead, Lithuania joined the 21st century, and the post-Communist world proved keen to change beyond recognition what was left of the old European one.

The brutality of the language, along with poor editing and undifferentiated attitudes both toward professional assessments and sporadic mass opinions, discouraged many gifted authors from writing political commentaries or otherwise contributing to online publications. It is possible that poor manners and sadomasochistic language were masks, hiding an intellectual and moral void, but the real reasons behind the confusion and uncertainty were the political void and lack of content, rather than merely an outbreak of stupidity.

In the 1990s, Lithuania had high hopes for a bright future; it had a grand narrative and a self-legitimizing discourse of its return to Europe. On a closer look at its internal debates, however, it appears that part of our bitter disappointment springs from a radical change of roles; as Oscar Wilde would have said, it is the horror of Ariel who sees in himself the mirror image of Caliban.

The country entered the phase of organized forgetting. Ours is an age of oblivion. Once, we were struck by Milan Kundera’s message in The Unbearable Lightness of Being that the sad news about the tragedy of Prague – as seen through Tereza’s photographs in Switzerland (where she and Tomas come to save their lives and future after the crushing of the Velvet Revolution of 1968) – turns out to be old news. This is exactly what is happening in Lithuania: the best of our culture and thought is old news. The country and its media are, sadly, confined to TV reality shows, vanity fair, and the private lives of public figures, which is just another term for celebrities.

This is not to say that Lithuania is incapable of good press and quality media. It is rather to suggest that the country seems to have next to nothing to remember and even less to celebrate but political scandals and the ups and downs of its political clowns.

Passport Jorunal, vol. 1