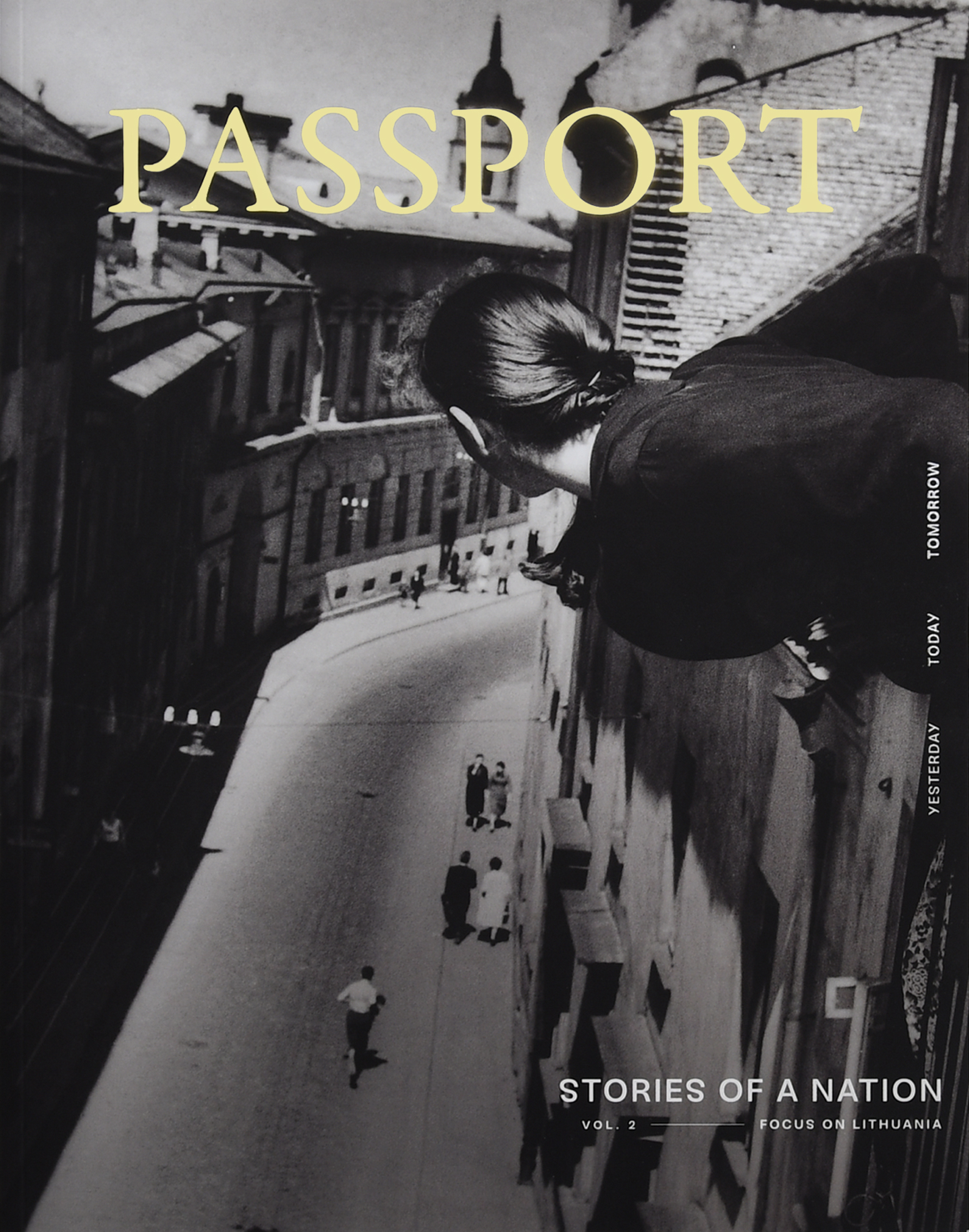

Doctor of Philosophy in Biochemistry

I don’t know of a single scientist who isn’t a curious person.

Urtė Neniškytė

Back to the Future

How would you describe your job to a teenager?

My research is actually quite related to the processes that happen in a teenage brain. During the first six months of our lives our brains are building synapses that are later optimised, leaving only the essential ones. This process is called synaptic pruning. Later, between the sixth and twelfth years of our lives, the process is paused. Then starts a very important stage of synaptic pruning, located in those parts of the brain that are responsible for our personality.

This is the reason teenagers are so rebellious – they’re trying to find themselves and their place in the world, they’re shaping their worldview. Their brains are removing the old synapses and replacing them with new ones. I’m searching for an answer as to what exactly determines which synapses are removed and which are kept – essentially, what shapes us into the people we are.

What influenced such a career choice?

I’m one of those people who arrives at decisions consciously and assesses all the benefits and drawbacks. So when choosing my studies I already knew this was not a field that would allow me to earn a lot of money. Although my parents and their friends had academic degrees, I didn’t feel any pressure when choosing a profession. Of course, the environment I grew up in had a lot of influence on me, but I only discussed my choice of profession once, with my father. He asked me if I want to earn money or do what interests me. I chose the latter, determined to think about how to achieve financial gain later.

It requires quite a lot of patience, doesn’t it?

Absolutely. I don’t know of a single scientist who isn’t a curious person. This profession requires perseverance and an inner flame. Curiosity and persistence are the qualities that lead us to our goal, stop us from getting complacent and encourage us to constantly search for answers. It’s probably the only reason why we scientists do what we do. After all, experiments in the lab will much more often fail than be successful. This resistance to failure can be cultivated, and then misfortune becomes second nature.

You spent eight years abroad and had traineeships in three different laboratories with divergent types of work and fields of research. What did this experience teach you?

First of all, communication skills. The ability to interact effectively is essential in any field, so I’m very glad I adapted fast. Mutual respect for your colleagues is very important, too. It doesn’t matter what your duties or position in the chain of command are – when leading a team you must take responsibility for a positive work environment.

Have you ever encountered prejudice from others?

Yes and no. As with everything, a lot is determined by your personality and ability to communicate with your colleagues. It’s unfair to attribute personal traits to an entire group. For example, when my mentor found out that I had decided to leave Italy and return to Lithuania, he was completely devastated. In his opinion, such a decision was the undoing of my talent and further career in science.

I remember when Lithuania joined the EMBO (European Molecular Biology Organization), Professor Virginijus Šikšnys came to one of the conferences all the way from Lithuania. After a brief conversation with him, my mentor came over to me and said, “You know, Urtė, I realised that you’re going to be okay!” So the world hears the name of Lithuania louder every day.

What needs to be done for more Lithuanians to follow in your footsteps?

If we’re speaking about professionals, the majority of them repatriate when they see the potential for self-actualisation. I myself went away because I wanted to acquire new skills and be able to contribute as much as possible on my return. After all, it’s always nice to return to a place where you feel needed. On the other hand, there’s an incentive too – the physical space that surrounds us. Lithuania just has more of it – nature, lakes, homesteads and other things like this are in our Lithuanian blood.

So I fully believe that once the governing of our state attracts more professionals, effective and useful decisions will be reached. It’s hard for me to comprehend the hyperbolic claim or attitude that we will manage to entice people to come back to Lithuania just by saying, “Come back and everything will be alright!”

That’s not how it’s supposed to be – everything needs a reason, a purpose.

Urtė Neniškytė

You said that during the first six years of our lives we adapt to our environment. Should we assume that later, after our environment or place of residence changes, there’s a danger of not fitting in?

The younger the child, the easier they adapt to their environment, because their brains are completely open – they are learning to live in this world. Older children have a harder time because their brains are already formed and adapted to a completely different life. I remember when I was 20, I went abroad for a couple of months. I felt plunged into a completely different, totally unfamiliar context. I didn’t even know where to buy a bus ticket. Of course, you can ask and find out, but that’s just one question among many you don’t immediately have answers to.

Although emigration and life abroad can be tamed, the brain is best adapted to life in the environment where you grew up. So it’s completely irrelevant how long you spend abroad – on return, everything is much easier and you can finally relax.